Born in 1922, Guy Hamilton was the second director to shape Bond’s cinematic journey. When he came on board to direct the first real designer bullet of the Bond series (1964’s Goldfinger) he steered a 007 bullet that would define everything that came after. Goldfinger did not just redefine Bond on his third spin of the movie wheel. It redefined action cinema. Hamilton’s subsequent Diamonds Are Forever, (1971), Live and Let Die (1973) and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974) were not just further entries in Bond’s cinematic output. They were the films that Hamilton enabled Bond in the 1960s and 1970s to fully echo the timbre, beats and essence of the decade they had to cinematically dominate.

The effect of Goldfinger on cinema, culture and of course the onscreen fortunes of James Bond 007 cannot be underestimated. It is not just 007 that emerges from the shadows at the beginning of Goldfinger. The modern-day blockbuster does too.

‘The dragons have changed. Fleming was always writing about the Russians as the villains and the Cold War. But life has gone on. And so the problem these days is to find the dragon because Bond is St. George. Ultimately, he is killing dragons for the benefit of mankind.’

guy hamilton, 1975

The first two Bond films are brilliant, youthful films, yet visually and narratively very static. They are pinned to a late 1950s Kennedy era in a decade of the chaps of empire, A-line skirts, and the older guard still pulling the strings, and a vestige of the 1950s that had arguably not yet found their feet yet, cinematically and culturally. As soon as we get to 1964 and Goldfinger suddenly the Bond series is about movement. We’ve got the Aston Martin DB5, Ken Adam’s moving sets, the titles project a new kinetic dawn of graphic design, Shirley Bassey’s anthem of a theme tune revolves and undulates, and when the film opens with a diver at a Miami hotel falling down into the water, the camera goes with it. That is down to Guy Hamilton opening up both the visual and pacing dynamic of Bond.

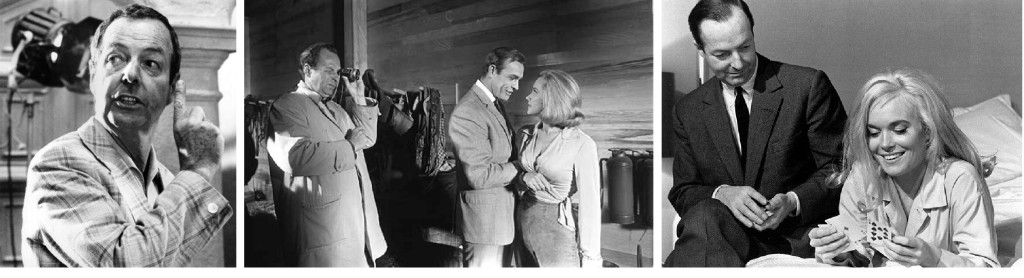

Goldfinger is one of the first really visual films of the 1960s. Terence Young’s brilliant Dr. No (1962) and From Russia with Love (1963) are still quite tied to that cerebral, dialogue-based spy world. We are told the story through dialogue. But in Goldfinger and under Hamilton’s command we are not told a woman’s going to be killed. We see her, painted in gold and dumped on a bed. It is a visual, adult and visceral currency Hamilton afforded the Bond franchise forever more.

A great many of the visual tics of Goldfinger are part of the lexicon of 1960s cinema. Bond waking up with Pussy Galore putting a gun to his face, Bond on the laser table, the DB5, Robert Brownjohn’s gilded titles, Bassey’s notes, a deadly hat and Shirley Eaton dead on the bed – they are all as much a vital beat of 20th century entertainment as they are when Bond turned a corner and cemented his future for decades. It was Hamilton who inherited Terence Young’s steadfast 007 recipe, but sourced and prepared the ingredients differently. He often dropped Bond into the United States of America with all its cultural clashes, pop-culture swipes and sense of modernity that was still exotic to European moviegoers. When he directs Live and Let Die, it is not a Blaxploitation hit he wants to emulate. It is The Godfather.

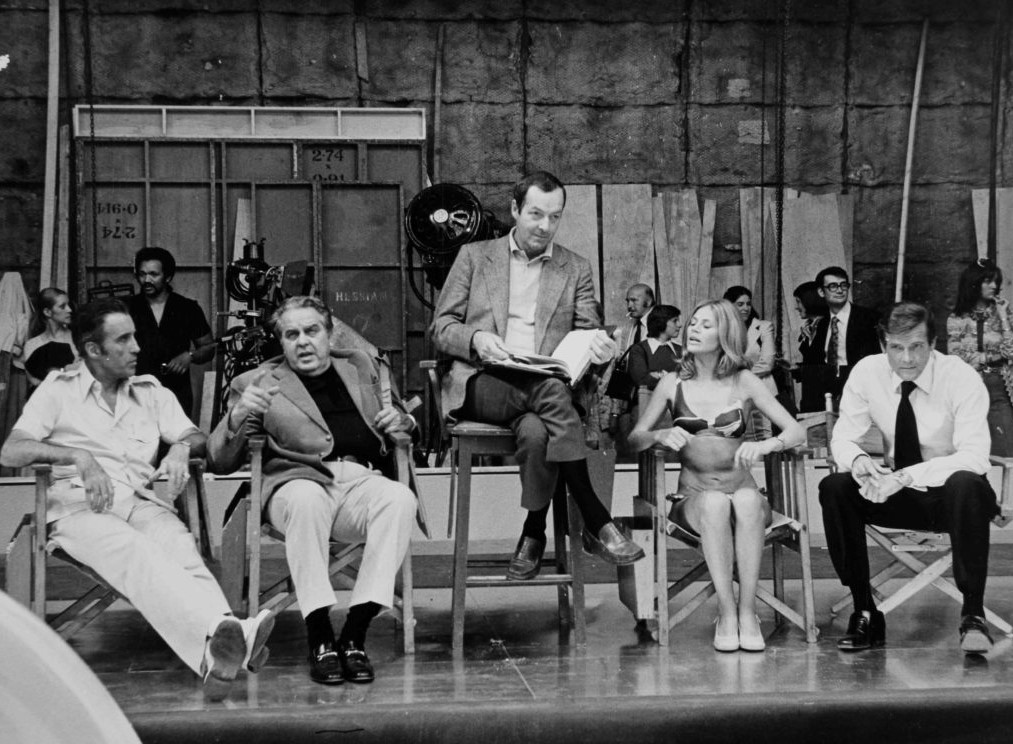

After a seven-year gap, Hamilton returned to direct Sean Connery’s [first] last spin of the Bond dice, 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever. He then continued and bedded Roger Moore into the role with the subsequent Live and Let Die (1973) and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). In all his Bond work, Hamilton gave Bond a cinematic head-start for two decades where 007 had to be at the top of his movie game or he may well have floundered at the box office. And he did so by placing Bond as the audience, an often rather British fish out of water battling new cities, new cultures and new technologies – be it Harlem, Las Vegas or Thailand. Blessed with cracking dialogue and pacing from screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz, the back-to-back trio of Hamilton’s three 1970s bullets are a rich run of adventures that weathered a less public rift between founding producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman. When EON Productions and Cubby went solo with 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me, it was Hamilton who ensured the series was left in a solid enough place for the public – and EON’s – confidence to move forward.

“We mourn the loss of our dear friend Guy Hamilton who firmly distilled the Bond formula in his much-celebrated direction of Goldfinger and continued to entertain audiences with Diamonds Are Forever, Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun. We celebrate his enormous contribution to the Bond films.”

BARBARA bROCCOLI & mICHAEL g. wILSON, APRIL 2016

Hamilton was often circled to return for other Bond movies (he was first approached for 1962’s Dr. No but reportedly turned it down) and was the first director attached to helm what became 1978’s Superman the Movie (a tax situation meant he had to ultimately pass on the reins to Richard Donner). Hamilton also directed Harry Saltzman’s Battle of Britain (1969) and possibly the best Harry Palmer film, Funeral in Berlin (1966) – designed by Ken Adam, shot at Pinewood Studios and scored by John Barry.

Other work included Alistair Sim’s An Inspector Calls (1954), The Party’s Over (1965), Force Ten from Navarone (1978) starring Harrison Ford and 1980’s The Mirror Crack’d which gave an early role to future Bond, Pierce Brosnan. In 1982 he returned to the world of Agatha Christie to direct possibly the best of the on-screen adaptations, Evil Under the Sun. The film is a delicious and meticulously plotted treat with Diana Rigg and Peter Ustinov on full sail and a cracking Cole Porter score.

In perhaps his best gift to the Bond franchise, Hamilton proved something that had yet to be proved for 007 himself – that you can successfully recast a Bond director and take the series forward. Again, it is the legacy of movement and momentum he gave to Bond.