Catching Bullets – Memoirs of a Bond Fan omitted Sean Connery’s second movie comeback as James Bond 007 for a variety of reasons. The main one being space. Fellow bullet-catching readers wondered just how this Bond commentator caught 1983’s rival Bond film. As its box-office challenger Octopussy was the starting pistol for this Bond fan’s personal journey with our man James, it now makes sense to address this missing sibling from the 007 movie barrel. And even more so as Sir Sean Connery now turns ninety and was the standalone, game-changing reason 1962’s Dr. No was never the final Bond film, but the first of a franchise that changed cinema.

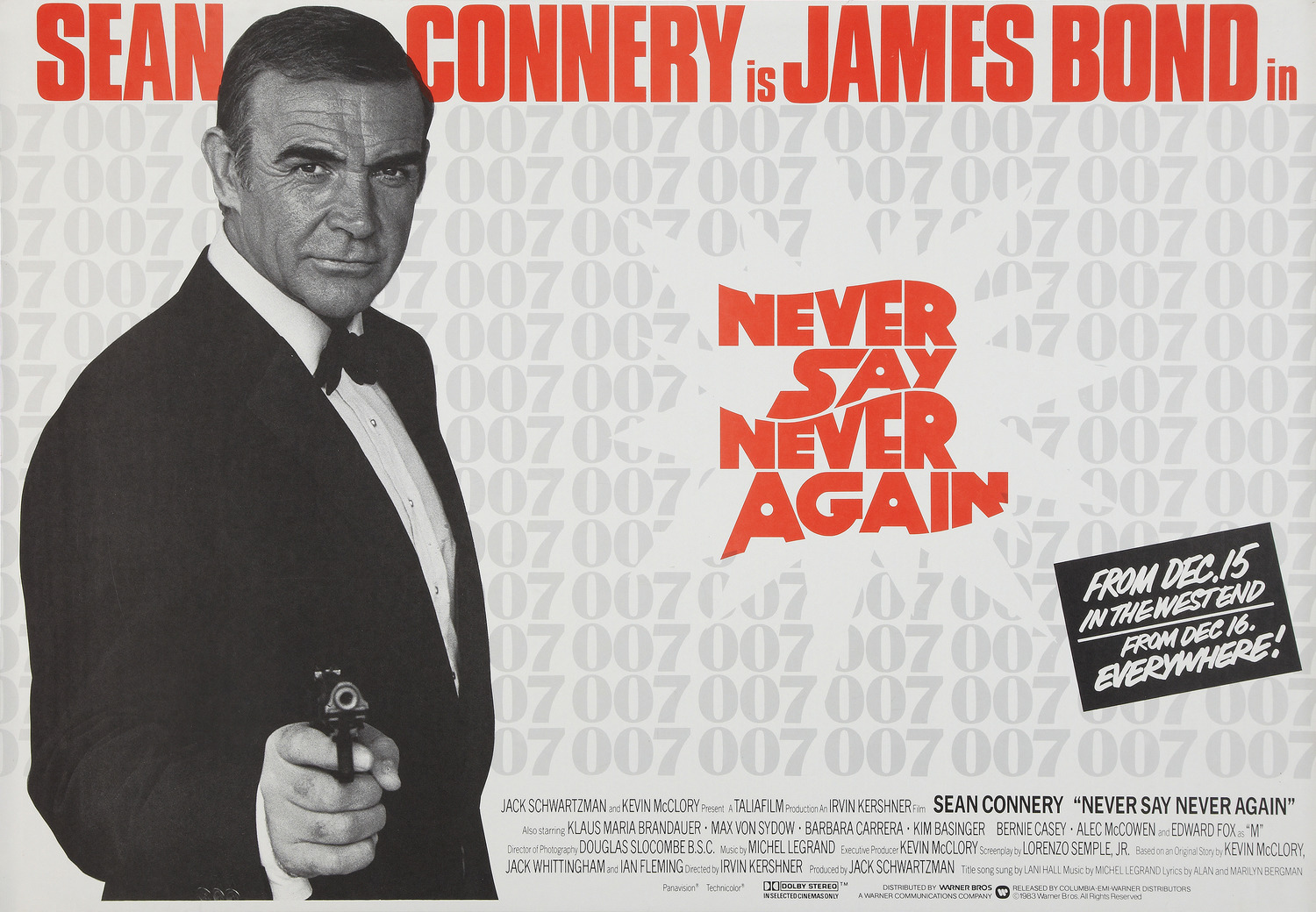

When NATO nuclear warheads go missing during a routine training exercise, a veteran James Bond (Sean Connery) has a hunch that involves the Bahamas, a red widow killer, SPECTRE darling Emilio Largo (Klaus Maria Brandauer) and his naïve charge, Domino (Kim Basinger).

‘My word. They don’t make them like this anymore.’

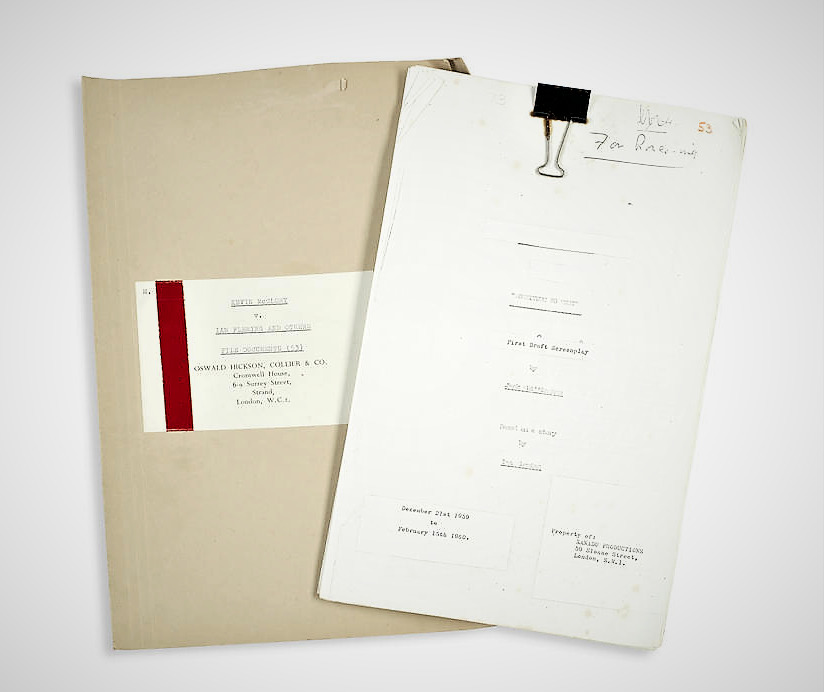

It is 1982. At both ends of the Home Counties studio belt of Britain, two rival Bond films are in production with an eye on a 1983 release. One stars Roger Moore in his sixth Bond bullet for producers EON Productions, Octopussy. The other stars his friend and role-colleague Sean Connery in Never Say Never Again. A legality twenty years before dictates that producer Kevin McClory and playwright Jack Whittingham ultimately share intellectual rights to the 1961 novel Thunderball with author Ian Fleming. McClory was now legitimately clear to produce his own Bond film – assuming he stuck to the characters, elements, and confines of the one novel. That project was initially a late 1950s screenplay draft called Longitude 78 West. In 1976 it becomes Warhead (having also been titled James Bond of the British Secret Service and credited to McClory, Whittingham and Fleming). Warhead is credited to author Len Deighton who works on the script with McClory and Connery for Branwell Film Productions (McClory’s Bahamas based company). The 1980s version which finally made it to the screen would eventually be called Never Say Never Again.

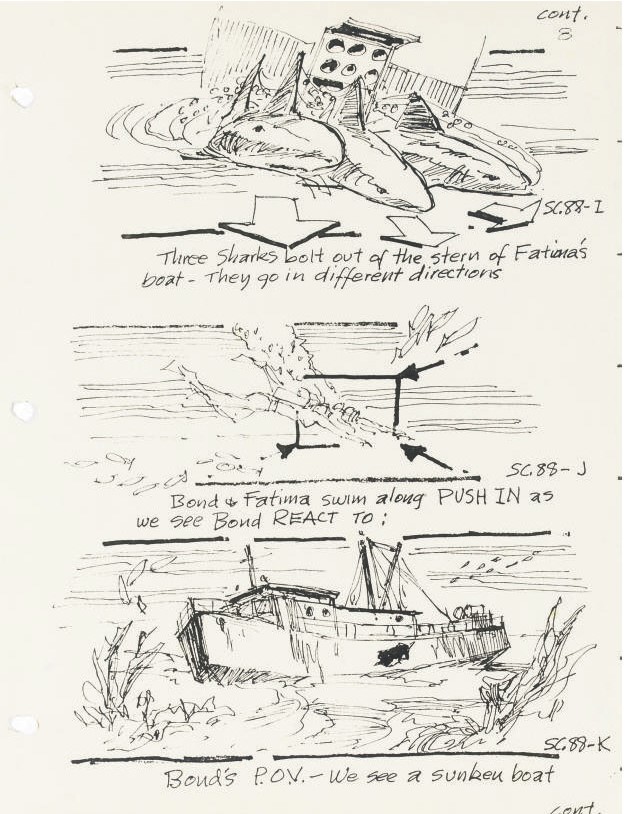

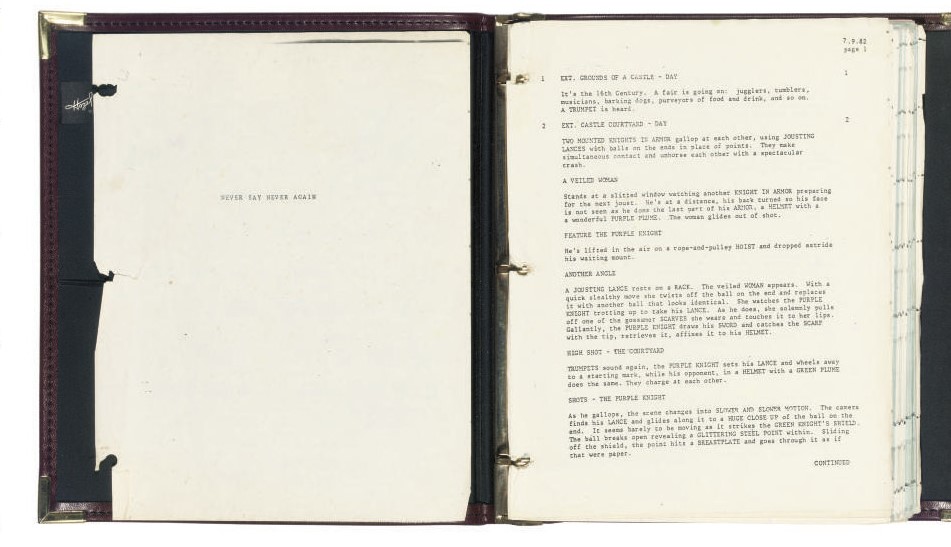

- An original draft of 1959’s LONGITUDE 78 WEST and producer Kevin McClory’s original 1982 shooting draft and storyboards for NEVER SAY NEVER AGAIN (based on JAMES BOND OF THE SECRET SERVICE) (Images © Christies / 2008)

Various Bond creative alumni who had worked on the EON Productions 007 project over the years were approached to take on the film’s key roles. The founding father of Bond editing and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service director Peter Hunt was once circled to helm. However, his loyalty to EON Productions and Albert R. Broccoli dictated a kind pass. Hunt instead became the second-unit director on The Jigsaw Man – a 1984 spy drama starring Michael Caine and directed by original Bond director, Terence Young. Other EON alumni were approached and also declined – often citing the same reason. Screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz was asked by Connery to take a look at the script. Mankiewicz later discusses in his memoirs (My Life as a Mankiewicz – An Insider’s Journey Through Hollywood, 2012) how his simple response had to be ‘I can’t’. However, when the film was at the rough-cut stage and needed fresh eyes, Connery again returned to the man who had not only written Diamonds are Forever, Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun, but also had left his fingerprints quietly on later Bond scripts of the era. This time Mankiewicz went to Cubby Broccoli who – with perhaps more grace than Connery himself was using across the early 1980s chat show circuit when it came to EON – responded with ‘Please do – and give him every suggestion’. Mankiewicz sadly describes in his book how Connery at the time was ‘a snake in the grass’ to do Never Say Never Again. His reasoning for returning to a rogue 007 film and the fingers-up which his Bond ’83 represented to the very House of Bond that launched the actor was no doubt manifold. Ownership, authorship, egos, creativity, bank balances, colleagues and time are strange bedfellows in Hollywood.

Connery had worked with director Irvin Kershner in A Fine Madness (1966) and had not only collaborated with producer Kevin McClory before on the original bullet Thunderball (1965) and its ditched attempts to be remade prior to 1983, he had played one of many clowns in McClory’s charity curio doc Circusia (1976) alongside Eric Clapton, Shirley MacLaine, Burgess Meredith and John Huston. Connery’s writer pals Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais (The Bank Job, Still Crazy) also provided an uncredited script polish. Famously, the Shrublands clinic gag about Bond passing a urine sample ‘from here’ was an in-joke nod to the same line from the comedy pair’s hit UK sitcom, Porridge. La Frenais and Clements also repeated the uncredited rewrite favour for 1996’s The Rock and the final film Sean played on and played up his British spy history.

‘I’m to eliminate all free radicals.’

Other previous Bond crew names to push on however with Never Say Never Again were dubbing sound mixer Norman Wanstall (who had helped pioneer the early sound tropes of Bond and won the Academy Award in 1965 for Goldfinger), stunt co-ordinator Vic Armstrong, stunt names including Bill Weston and Roy Alon, music producer Herb Alpert (who had steered the opening titles of 1967’s Casino Royale and whose A&M Records signing Brasil ’66 performed Bacharach’s evergreen ‘The Look of Love’ at the 1968 Academy Awards telecast – before Alpert married band member and title song performer, Lani Hall), underwater co-ordinator Ricou Browning, actress Valerie Leon (The Spy Who Loved Me) and actors Manning Redwood (A View to a Kill), Billy J. Williams (Licence to Kill) and Billy J. Mitchell (GoldenEye) who were about to move onto EON Bond post Connery ’83.

Maybe the biggest casting curio of Never Say Never Again casting is also the film’s smallest cameo – and the only name other than Connery to have officially acted in both movie versions of Thunderball. With Italian character actor Robert Rietty’s brief appearance as a disgruntled Italian Minister, the villains, allies and croupiers of least six previous Bond films are reunited in Never Say Never Again – because it was the voiceover genius Rietty that had technically played them all. For a film that holds many crossover loopholes, it was Rietty who famously voiced villain Emilio Largo in the original Thunderball. This bullet catcher would have been playful and had that original Largo (Adolfo Celi) dub his scene here in 1983. Rietty was fresh off vocal duties for 1981’s bullet For Your Eyes Only – having voiced the bald pre-title figure in the wheelchair Roger Moore drops down a Beckton Gas Works chimney – and which may or may not have been an House of Bond dig at Kevin McClory and just what the movie world thought of his perceived attempts to ring out the Thunderball sponge and try to hold certain rights, characters and properties creative prisoners forever more. Thirty years later in November 2013 and after the Irish producer’s 2006 death, the McClory estate finally settled with Bond rights holders Danjaq and MGM to bring all the 007 properties and ownerships under one roof. Cue 2015’s Spectre.

‘Do you know him?

Oh, yes. Double-O-Seven.’

One of the overlooked beats of this imitation bullet, is the wholly rich heritage and achievements of the key creatives responsible for it. This is a Bond film lensed by Douglas Slocombe (Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Italian Job, Rollerball), co-written by Lorenzo Semple Jr. (The Parallax View, Papillon, Batman), scored by Michel Legrand (The Thomas Crown Affair, The Summer of ’42), costume designed by Charles Knode (Blade Runner and later Spymaker – The Secret Life of Ian Fleming), production designed by Stephen B. Grimes (Ryan’s Daughter, The Way We Were) and directed by Irvin Kershner who’d already skippered one of the most key titles of the decade and indeed century, The Empire Strikes Back (1980). These were an artistic ensemble the Bond series would not arguably have pushed for again until the Daniel Craig era and its coy need to fill creative roles with the world’s best movie craftsmen and women.

Nevertheless, the end-result of Never Say Never Again is not quite the Bond sum of those parts. Producer Jack Schwartzman was not an experienced producer of big cinema. Production stumbled accordingly – with Connery himself upping his own producer management he had already ensured for his return to try and steer the precarious film to a successful completion. Kevin McClory himself had instincts and certainly an ardent drive. Yet, Never Say Never Again rarely plays like the return of an independent James Bond story as it is always pitched first and foremost as the return of Sean Connery. And – to be fair – for the world’s movie audiences of 1983 that was enough. This was hardly the first Bond film to be greenlit on the back of Connery and the box-office’s love for Scotland’s first action hero of cinema. The added irony is that Never Say Never Again is a Roger Moore Bond film in Sean Connery’s sweatpants and dungarees.

‘Do you lose as gracefully as you win?’

‘I don’t know. I’ve never lost.’

Original Never Say Never Again artwork by Renato Casaro

There is a sense with Connery that his first return to the role with Diamonds are Forever (1971) was a good experience for him after the strained production experience of his previous You Only Live Twice (1967). This is the Sean of Diamonds are Forever – once again launching a rich movie decade for him by letting Bond prove he still has the leading man chops and star power to take a movie to audiences. Never Say Never Again was still a massive success – just ultimately pipped to the Bond ’83 winner’s podium by Roger Moore’s Octopussy. A certain generation of Bond fans remember all too well those chunky Warner Brothers VHS rental boxes and how this replica bullet always shared video-store space with its adoptive siblings For Your Eyes Only, Octopussy and A View to a Kill. The BBC rather than the usual ITV covered the London premiere for a special broadcast and Renato Casaro’s poster artwork for some of the ad campaign was retro-glorious. As was his artwork for the other Bond film that year including the delicious Octopussy teaser and its tentacled pulp brilliance.

Never Say Never Again proves the more familiar EON and Broccoli steered tropes, tricks and grip on the franchise are not just idle dressing shackled to proprietorship. They are the very DNA of James Bond onscreen. It is part of a celluloid template that author Ian Fleming even threaded into his latter 007 novels as the early films took off and Connery took the character from literature sensation to cinema’s biggest phenomenon of the 1960s. Having rights to the genome of one chapter of a franchise does not guarantee an artistic landslide. With a mysterious unseen pre-title jousting sequence allegedly and enticingly consigned to the cutting room floor, Never Say Never Again already opens on the backfoot without a stylistic fanfare and graphical overture. The beats of a Bond film are there – a feverish ‘M’, Home Counties oil-paintings above ornate mantelpieces, a love-sick Moneypenny in a Princess Diana puff-blouse, over-English quartermasters panicking about their kit and the old days, Bond Arriving™ at various jet-set airports, a Felix Leiter first presented as threat, yacht-strewn ports, a European villain more tech-savvy than Bond and a nuclear countdown. Yet, the film also oddly lacks the momentum of familiarity, despite holding some worthy beats of its own. The tango dance, Brandaeur’s deceptively chilling villain, the Shrublands fight, the bike chase and Fatima Blush’s sadistic demands for a sexual Trip Advisor review from Bond are all noble beats.

However, there is some connective tissue missing. One of the film’s small stumbles is its tone. A spa massage scene that would play as exotic and alien in You Only Live Twice now feels like a seedy grope in Fitness First. In a real 1983 world of nuclear disarmament protests and Cold War defiance mutating with Japanese tech and gaming, the film and its SPECTRE treachery has no political or civilian consequence. Extortion is always a hard sell onscreen. Like videogames. Octopussy showed the human face and consequence of the people its story bomb would destroy. Never Say Never Again just revels in those flying-missiles-over-land FX shots that Superman had been using for years whilst world leaders huddle together like Batman ’66 dignitaries.

The film is unquestionably loaded with 1980s tics. And more so than Octopussy – with its wilfully classic components, majestic locations, steam trains, hot air balloons and colonial trappings. But Never Say Never Again’s anchoring to a 1960s Cold War caper in the era of Lucas and Spielberg is telling. Long before Cary Joji Fukunaga became the first American to direct an EON Bond with No Time to Die, Irvin Kershner – who also taught both Lucas and Spielberg at film school – was the first US captain of a Bond. And it shows with a slight American posture to Never Say Never Again. ‘London’ is absent, American generals litter the international drama, consumerism turns Largo’s yacht from a Cold War missile hiding threat to a disco-tech show of bling, one of the 1980s most famous American actresses plays opposite Connery, the villain’s wealth and society soirees feel more Bruce Wayne than Blofeld, and the arcade game culture, Yamaha products and locations have a gameshow prize tinge to them rather than some far flung, exotic novelty. And did we mention the very 1980s Donald Trump connection?!

‘Keep dancing!’

It is quite apt screenwriter Lorenzo Semple Jr. and director Kershner rechristen the former Disco Volante to ‘The Flying Saucer’ in Never Say Never Again. The yacht’s own 1980s history soon became a crazy b-movie of its own. There are not many moments in any 007 timeline where Freddie Mercury and Queen record a track in dedication to a boat appearing in a Bond movie. However, later in 1989 that is exactly what happened when Mercury and the band recorded their pumping ode to the $100m yacht and 1980s excess entitled ‘Khashoggi’s Ship’ (The Miracle album, 1989). The Benetti built yacht christened ‘Nabila’ was first built in 1980 for Saudi billionaire, Adnan Khashoggi (the ‘A.K.’ thanked in the end credits). After the Sultan of Brunei subsequently took over the ship for a time, the next owner was a man called Donald Trump – who then clearly bypassed official SPECTRE etiquette by rechristening the ‘Nabili’ to the somewhat less delicate, less mysterious and less Fleming sounding ‘The Trump Princess’. So far, so very Largo. This bullet catcher is not sure if Kiss ever got round to their stadium-blaring anthem to Octopussy’s Barge before it was sold to Vladimir Putin, but that one yacht from Never Say Never Again has seen off more jet-set villains than Sean Connery himself. The 1980s excess that the boat epitomises then went full circle when Martin Scorsese knocks the Manhattan excess of the Trumps of this world with DiCaprio’s The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) not only owning his own yacht, but the character even has ‘Goldfinger’ covered by soul-queen Sharon Jones at his wedding.

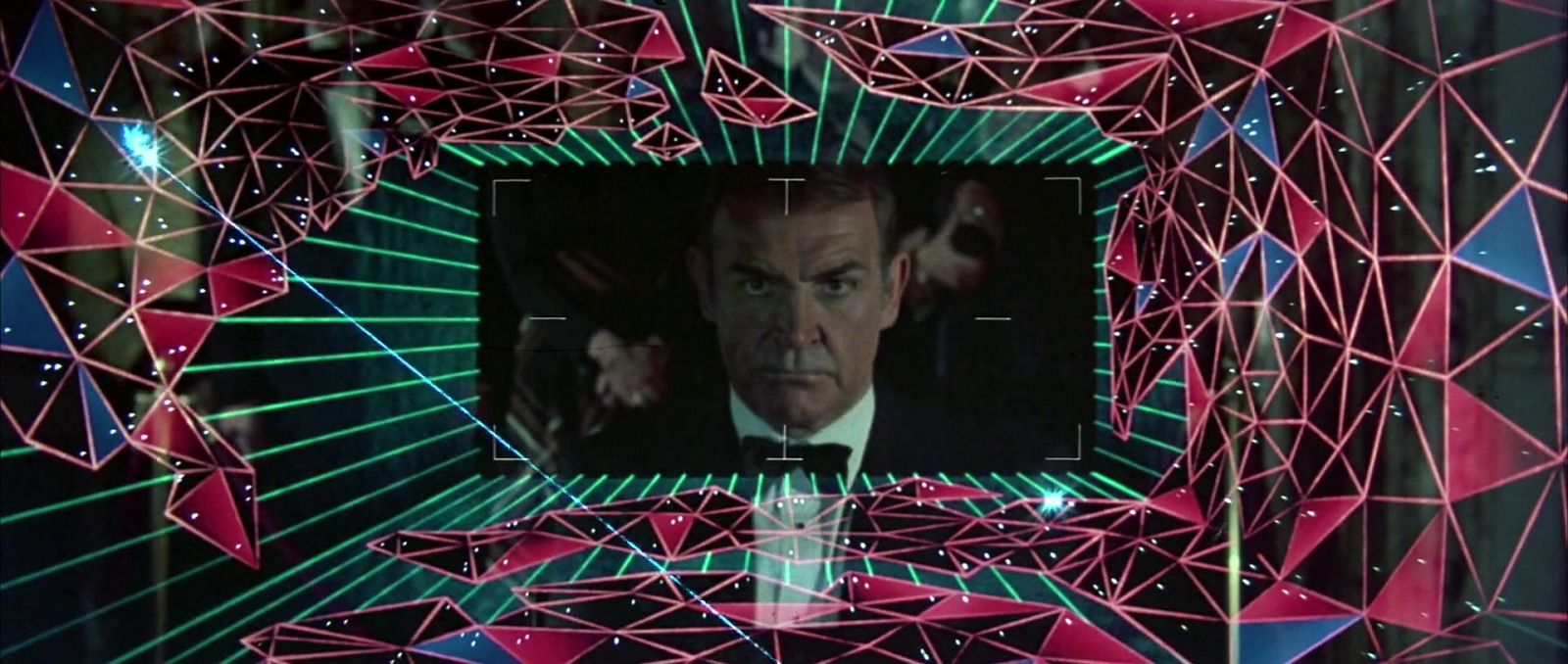

Nearly four decades on and as memories of pan and scanned VHS tapes and grainy, cropped TV broadcasts of the film fade for one generation that made the film often play like a bad 4:3 TV movie, Douglas Slocombe’s HD cinematography is easily now one of the rich takeaways of Never Say Never Again. Warm-tinged home-counties hues, crystal-clear corridors, antique gold trim and John Glen era US generals and knitwear-clad sailor villains populate the visuals. And Slocombe’s use of red neon, software, carpets, lasers, retina scans, SPECTRE tech and branding, submarine lighting, end titles and Fatima Blush’s devilish spider-woman ballgowns and Renault 5 is wilfully rife. The film that misses a bloody gunbarrel opening gambit makes up for it with its blood red motifs. Barbara Carrera’s role as SPECTRE’s psycho nurse Number 12 is easily one of the film’s victories. She also gets some of Slocombe’s best photography as her evil under the Nassau sun villainy is all about her outlandish beach hats, deadly boots, multi-tasking side-eyes and viper mind.

Nearly four decades on and as memories of pan and scanned VHS tapes and grainy, cropped TV broadcasts of the film fade for one generation that made the film often play like a bad 4:3 TV movie, Douglas Slocombe’s HD cinematography is easily now one of the rich takeaways of Never Say Never Again. Warm-tinged home-counties hues, crystal-clear corridors, antique gold trim and John Glen era US generals and knitwear-clad sailor villains populate the visuals. And Slocombe’s use of red neon, software, carpets, lasers, retina scans, SPECTRE tech and branding, submarine lighting, end titles and Fatima Blush’s devilish spider-woman ballgowns and Renault 5 is wilfully rife. The film that misses a bloody gunbarrel opening gambit makes up for it with its blood red motifs. Barbara Carrera’s role as SPECTRE’s psycho nurse Number 12 is easily one of the film’s victories. She also gets some of Slocombe’s best photography as her evil under the Nassau sun villainy is all about her outlandish beach hats, deadly boots, multi-tasking side-eyes and viper mind.

The French Riviera has that wonderful early 1980s Cinzano Bianco tinge to it. It plays like the wonderful movie France and Europe of Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo (1977) and 1981’s Condorman (also featuring Barbara Carrera and Bond stunt legend Remy Julienne). The kit, missile-launched jetpacks, Yamaha Turbo motorbike and Atari minded videogames are perhaps more fun than the sets. Whilst it was no doubt McClory, Kershner and his team being mindful of youth culture of the time, those features oddly remind more of the glories of Thunderball and Bond-mania than some ruse to throw 007 into a game of Pong and have Kim Basinger’s tiger-print nod to 1980s fitness videos. A duel of wits and those dinner scene jabs between Bond and his villain are here replaced by a Firefox or WarGames videogame joust (early drafts of the film actually featured medieval jousting) – as Bond plays what feels like the same Atari game Robert Vaughn plays in the same year’s Superman III (with actor Gavin O’Herlihy playing the same misled stooge who helps the villains kickstart their cyber-crimes in both films).

The whole design of Never Say Never Again has a cost-cutting tenet of dressing existing ballrooms, houses, yachts, society boltholes and clinics rather than making the Ken Adam statement of newly built modernism. By the final act, Connery ’83 is tripped by its very founding – it feels like a re-tread of Thunderball’s beats rather than going up a game level to be its own statement. Thunderball’s director Terence Young always deemed the then new underwater scenes slowed down his 1965 bullet. The film’s underwater director Ricou Browning may return from Thunderball for some crisply shot submerged subterfuge, but the irony is they are all over too quickly.

Which is not something one could level at legendary composer, Michel Legrand. A 1960s easy-listening and jazz-minded tunesmith is not a million miles from the great Bond composer John Barry. However, Legrand peppers the film with faux-tango orchestrations, Euro-jazz synths and lounge-bar seductions by 1980s Manhattan saxophones to craft a somewhat incongruous score. He also fails to provide a signature tune for Bond. And nothing screams Connery and a near-naked Kim Basinger on horseback fleeing an Arab flesh bazaar more than an uber-fast jazzercize riff. But when the score echoes the nightclub sleaze of George Martin’s Live and Let Die and the early 1980s romance of Bill Conti’s For Your Eyes Only, we will almost forgive it for being some Thunderbirds meets Carry on Emmanuelle rarity of Bond scoring.

‘You know that making love to Fatima was the greatest pleasure of your life!’

Bond ’83 II has the illustrious honour of becoming the first Bond film to sound like a Pierce Brosnan 007 title. Warhead was a title producer Kevin McClory clearly found hard to decommission. With eyes on the momentum Broccoli and Saltzman had created for 007, pop-culture and cinema, he later attempted to remake his remake in the late 1980s as Warhead 8 and in the 1990s as Warhead 2000. McClory’s possible mistake was thinking that – whilst he had a genuine legal claim to Fleming’s Thunderball novel – he did not actually have any rights to create his own continuing James Bond franchise. Despite the shining presence of Sean Connery, perhaps Never Say Never Again’s biggest drawback is how it is untethered to any other Bond film. It misses the continuity of Bond’s Whitehall colleagues, Pinewood Studios, Ken Adam’s lounges, John Barry’s brass and strings, Maurice Binder’s titles, an Aston Martin, those double-tufted SIS leather doors and that all-important end-credit promise JAMES BOND WILL RETURN. As the official series contemplates loading its twenty-fifth bullet into the crosshairs of cinema once again, this imitation bullet only has copy and paste in its arsenal.

Despite this, there is a great bounce to Connery in Never Say Never Again. As Daniel Craig now straddles three decades in the job and looks to end his own Bond tenure the same age Sean was when he returned in 1983, it is still Connery that spanned four decades in the role. He said never again again for 2005’s James Bond 007: From Russia with Love – where he clearly made use of those Atari videogame sessions with Brandauer’s Largo to return to voice 007 for EA Games. Connery may have self-pressed that ejector seat button to distance himself from the role more than once. But when he did, he rose higher and further than his other Bond successors combined. He did not have to do Never Say Never Again. His 1980s was about to win an Oscar, a Spielberg role and a submarine. His love, loyalty, business, and ownership of the 007 role clearly dictated otherwise. The film was also one of his pet projects too. Whilst some artistic elements do not quite meet in the middle on the film and more scenes with villain Klaus Maria Brandauer are sorely missed, Connery’s hold and sparkle in the role is still tenacious. He avoids playing it as retired veteran spy as he follows Roger Moore’s 1980s Bond to become almost godfather and warden to Kim Basinger’s family traumas. This is a Bond not past his prime but enjoying the last act of it.

Mark O’Connell is the author of Catching Bullets – Memoirs of a Bond Fan (Splendid Books).

SEAN CONNERY at 90 – CELEBRATING THE FIRST KNIGHT OF ACTION CINEMA by Mark O’Connell