When it comes to James Bond artists, names such as composer John Barry, designer Ken Adam and editor Peter Hunt are a given – rightfully etched in pop-culture stone forever more. But are names such as Marjory Cornelius, Julie Harris, Elizabeth Waller, Elsa Fennell, Tiny Nicholls, Emma Porteous, Lindy Hemming, Jany Temime and Suttirat Anne Larlarb just as familiar? They should be. Because for every time a James Bond film was scored by Barry, housed by Adam or cut by Hunt, he was wearing the wardrobe choices of those and 007’s other mistresses and masters of costume. For nearly seven decades, the history of Bond onscreen has been the history of costume design and both male and female tailoring.

As the sartorial curatorials of online Bond fandom continue to dissect each and every piece of 007’s costuming – often well before a new Bond film is released – as well as make great social media strides to document the merchandise ownership of Bond couture, the world of 007’s costuming is ever salient. And it is nothing new. The slick Dressed to Kill (Flammarion, 1996) was one of the first great publications to properly analyse, contextualise and understand the clothing missions of our man James – within a cultural, political and fashion context. And in recent times, From Tailors with Love: An Evolution of Menswear Through the Bond Films (Matt Spaiser & Peter Brooker, Bear Manor Media, 2021) has passionately and knowingly updated the literary documentation of Bond’s three-piece glories. As Matt Vaughn’s Kingsmen films proved, there is great fascination in the retro slacks and tweed twists of character of the movie spy world. The Kingsmen films alone are predicated on the Mr. Porter, Savile Row finesse, shop windows and wish fulfilment that Bond too provides. Whilst Bond is screaming out for a regular tailor scene stealer, Kingsmen used a cutters as the very narrative launch pad for its caper.

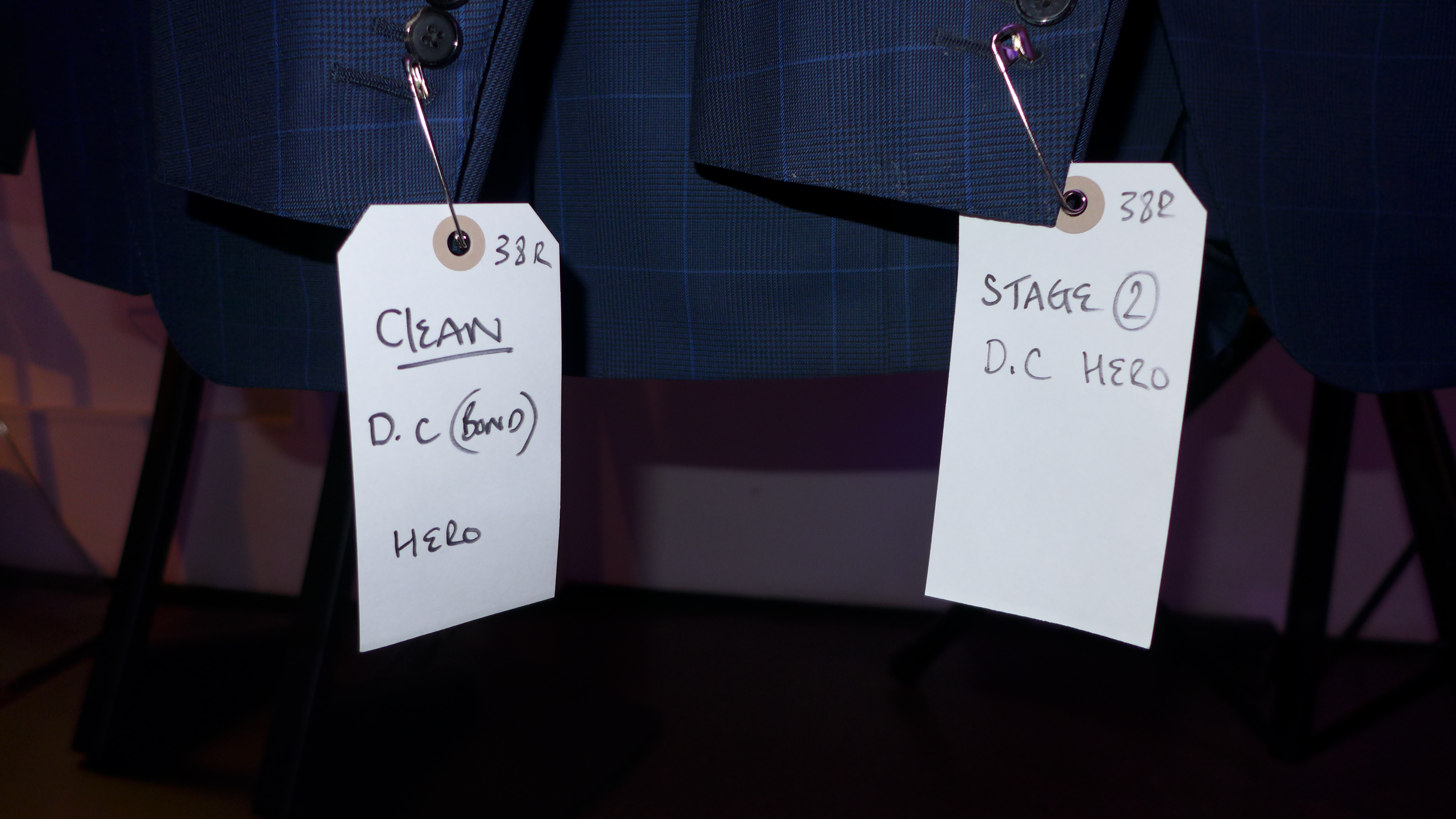

Tom Ford’s Prince of Wales check suit for No Time to Die / Photo © Mark O’Connell

Wearing or emulating the Bond looks has proved great social media currency with the fun, brilliantly addictive cosplay fantasy of it all. Yet, it sometimes overlooks the whys and hows of costume design, the history of certain cuts, how lengths and widths can be cultural and sexual, how fabrics, movie and gender history itself all feed into the decisions made on a gown or suit that is ultimately only seen on screen for four minutes. With Bloomsbury Academic’s Fashioning James Bond – Costume, Gender and Identity in the World of 007, author Llewella Chapman sets to cut a new template of Bond costume study. It is one that embroiders a wide world of known and lesser known characters, great study and cinematic application. And it is one that reads the other side of Bond’s clothing label – the women.

‘The understanding of the agency and labour behind realizing costumes for the Bond films also reveals itself when closely analysing the costume designs, where available, and the costumes as they appear in the final film’.

Llewella Chapman, Fashioning James Bond – Costume, Gender and Identity in the World of 007

With the chronology of Bond costume design, purchasing and evolution lined up like carefully curated hangers on a Bond history rail, Chapman’s book rethreads the clothing history of a franchise. In what could have been a cluttered and busy walk-in wardrobe of study, Fashioning James Bond has a crisp, accessible structure. It lets you into its suited web of sin. Immediately, the characters, sometimes rivalries, pay gaps and last minute creative decisions forge a rich, fascinating and always fun story. This is a tale of credited ‘fashion consultants’ actually being Bond’s costume designers and the fashion house histories – aside from Bond – that are often as eventful and larger-than-life as any Lewis Gilbert Bond caper.

Like the fine detail on a GoldenEye Brioni suit, Oscar de le Renta gown from Licence to Kill or Angelo Vitucci piece from The Spy Who Loved Me, the glory of Chapman’s project here is in the research stitching and the academic fabric of her execution. Reminding of the successful sense of project and record of Some Kind of Hero – The Remarkable Story of the James Bond Films (2015, Matthew Field and Ajay Chowdhury, The History Press), Fashioning James Bond is sewn together with constant small insight that becomes a three-piece suit and act with a deep sense of project in its pockets. Chapman reminds of the jewelers who return two decades later, that high street merchandise is nothing new and that all Bond design and creativity has many influences – including its own history, and that of its creators. She knows that all costuming is ultimately showbusiness, a mirage that only has to be right for the camera or the frame. Echoing the make do and mend nature of all filmmaking, Teri Hatcher remembers her painful gaffer-taped chest in Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) and the Velcro and 160 fasteners used to try and get Jodie Tillen’s sumptious ‘Rip-Away Hem Dress’ to tear in half when the story need arises in Licence to Kill (1989). And whilst it is not new to this bullet catcher, top Bond ’83 points go to Chapman for regaling the lovely anecdote of the two Singh brothers from Peterborough who answer a call from EON Productions for local experts in turban tying when no-one on Octopussy is sure how to correctly secure the headpieces.

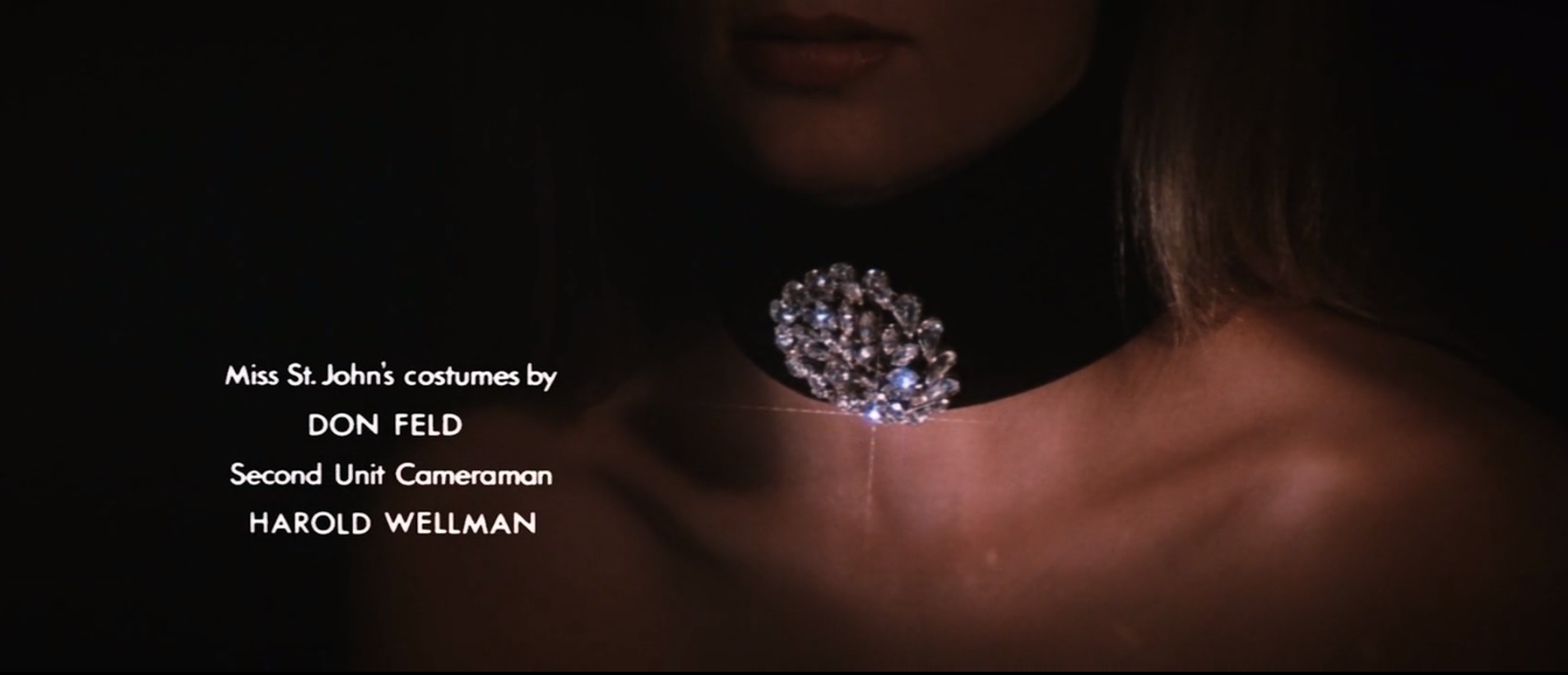

Partly suspecting Chapman and I share a great love for the kitsch gem that is Diamonds are Forever, you know Fashioning James Bond is a no sale-rail of a study when it briefly details the wig work of the 1971 Bond bullet. Actress Jill St. John had her own wig business at the time of production so went on a ‘wig promotion tour’ of Texas to the department stores. I want to live in a world where the wigs of Diamonds are Forever go on a tour of Texas! What follows with Chapman’s insight into designer Donfeld and the original script notes and scribbled suggestions is quietly delicious. As is the suggestion that maybe one of St. John’s own wigs was used when Charles Gray’s Blofeld sashays away in drag in the 1971 classic. The Blofeld and Donfeld Show is something the world desperately needs!

Possibly Chapman sometimes misses the fashion of Bond’s fashioning. And she is not alone. Many Bond costuming works and analysis cut around the sartorial zeitgeist surrounding the costume choices. The Britpop 1990s facilitated a renewed curiosity and magazine cover interest in the suited heroes of British retro culture. It is why the brilliant Carver media party costumes of Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) hold a modish swagger alongside their painstakingly designed use of original, non-copyrighted newspaper prints for all those Hamburg wine waiters. However, Chapman’s eye is very much on the industry fashions of tailoring and design. And the fashions of gender. And all those rich players of 007 fashion along the way that have been overlooked. Fashioning James Bond is as much a history of those fashionistas as it is one of 007’s togs, how they often straddled the old and new ways in their own worlds and couture house histories themselves before they even attempted to do similar for Bond costume design.

Chapman has painstakingly returned to the script and design archives. She understands how the original screenplay notes on a villain’s look or leading lady’s couture changes – and more importantly the detail is in where and why that change happened. Octopussy‘s Kamal Khan is script-described in 1982 as ‘a striking figure in his wine-coloured turban and forked beard’ until western actor Louis Jourdan took the role. George Lazenby has the most costume changes for any Bond in a single film. And costume designer Lindy Hemming (GoldenEye through to Casino Royale) lends Chapman great insight. Famke Janssen’s costumes on GoldenEye were meant to be ‘Cruella [de Ville] meets Morticia [Addams]’ and Isabella Scorupco had to alternatively be that of a ‘non-wealthy Russian worker’.

Tom Ford’s 38R suit rail for Daniel Craig and Spectre (2015) / Photo © Mark O’Connell

As some folk today cry that Bond clothing has got way too ‘high end’, Chapman reminds that is not always true. From 1961 onwards, this book underlines how many high street names fed into Bond too. In the Craig era of Orlebar Brown, Tom Ford, N. Peal, Sunspel and Crocket & Jones shoe-wear it is easy to overlook how this merchandise minded, sub-industry of Bond fashion has always been there. The clothing industry of Bond – both onscreen and on the store rail – is no new design of commerce and promotion. Norvic’s Bond shoes for Goldfinger (1964), Morley’s misfired ‘007 Underwear for Men’ circa Thunderball (1965), Galeries Lafayette’s Goldfinger accessories in 1964, and the Vogue Pattern Books accompanying On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) – Chapman documents how whilst it is not N. Peal via No Time to Die‘s costume designer Suttirat Larlarb that was the only access point for women to take the Bond clothing home with them. Its tonal template OHMSS was the first Bond bullet where EON Productions really targeted the women in the audience. Ladies Home Journal detailed the patterning of the Angels of Death’s attire, Arts Galore offered punters the brave option of a replica of Tracy’s wedding ring, and Berketex Brides crafted a recreation of the Portuguese wedding dress at 50 guineas. They didn’t sell well. But Chapman understands why the discussion and inclusion is vital.

Fashioning James Bond is neither a stodgy cultural look at gender nor is it weighed down with theory. It is more a worthy and much needed tribute to that ‘agency’ and toil of those backroom names, seamstresses, buyers and ideas people who create the very first thing we see on a Bond film, yet often the last element that gets celebrated. Despite the weight of these detail and research findings, there is a lightness to the fabric of this book. It is written by someone who knows their 007. And Fashioning James Bond is not just the history of Bond fashion. It is a slick document of different eras of British, European and American tailoring blended in with the realities of movie making on a budget and timescale, how sourcing fabrics is as much of a challenge as designing them, how the addition of a pocket or a diamond turns a look into an icon, and how Commander Bond is always at the sartorial epicentre of all decisions and fashion reckoning. From anecdotes about the cutters of London’s W1 to the tailoring wars, the boutique rivalries and the unwieldy eccentrics through to how a Bond actor walks into that world and the ideas bounce about again (‘Moore and Craig have possessed more agency over the way they have been costumed’), this is a cracking study of what is more than brand identity and onscreen heroism.

Fashioning James Bond – Costume Gender and Identity in the World of 007 by Llewella Chapman is out now and available from Bloomsbury Academic publishing.