With a Mind to Kill launches in London, May 2022 / Photo © Mark O’Connell

‘Jamaica had let him leave reluctantly’.

With a Mind to Kill

In an era of prequels, reboots and retro-refitted timelines, the literary 007 has long played suavely loose with the original order of business as prescribed by original author, Ian Fleming. For a pop-culture behemoth who has always moved forwards throughout his cinematic incarnations – give or take a plot-necessary flashback here and there – the written 007 has however long operated in a multi-verse of contrasting eras and shifting historical backdrops. After Sebastian Faulks’ Devil May Care (2008) pitched Bond into 1967, Jeffrey Deaver’s Carte Blanche (2011) aimed at 2011, and William Boyd’s Solo (2013) pinned itself to 1969, author Anthony Horowitz (Stormbreaker, Moriarty) was tasked by Ian Fleming Publications to steer Bond back to the second Elizabethan dawn of the late 1950s and early 1960s. After his celebrated Trigger Mortis (Orion Books, 2015) and Forever and a Day (Jonathan Cape, 2018) successfully took Fleming’s spy into a new successful era of publishing – whilst straddling and wholly understanding the more vintage beats of Bond’s world – Horowitz’s third literary 007 bullet now follows the events of the final Fleming novel, The Man With The Golden Gun (1965). Less joining the dots that already exist, Horowitz rearranges them like gambling chips on baize felt. And he does so most skillfully.

It is Spring 1964. Black roses, black Daimlers and some black souls are bringing scant light to a south coast funeral for Admiral Sir Miles Messervy. Known to very few as ‘M’, his death at the hands of his poster spy James Bond has sent curious ripples through Whitehall, Moscow and even the mind of 007 himself. Bond has been following his 2021 movie self’s advice and recuperating in Jamaica with Mary Goodnight before he is ordered back to London to face the Cold War music – and some surprising new notes that see Horowitz effortlessly turn a thunderball into a curveball.

‘The name joined all the others in the cemetery carved in stone.’

With a Mind to Kill

With the mortar and political implications barely dry on the new Berlin Wall, Bond is served a penance for his actions. He must return to being an undercover duke of Hazard in Khruschev’s Russia. Once again the empirical regalia of Bond’s Great Britain is usurped by granite effirgies to Lenin, an ever impoverished state and an iron safety curtain has dropped against western thinking, movement and culture. The current day political prescience of With a Mind to Kill is almost chilling. Just as Fleming’s own notations about the former Soviet Union, Britain and NATO are disturbingly relevant as they ever were, this is a work that very feasibly knows exactly why it introduces a Colonel Boris and has its own mind on a future Britain that may indeed one day share Bond’s ‘acidie’ and mental milaise about itself on the world stage. Like all good period works pinned to a narrative past, it is the now where such commentary is meant to create the same unease and discomfort Bond himself is suffering after the events of The Man with the Golden Gun.

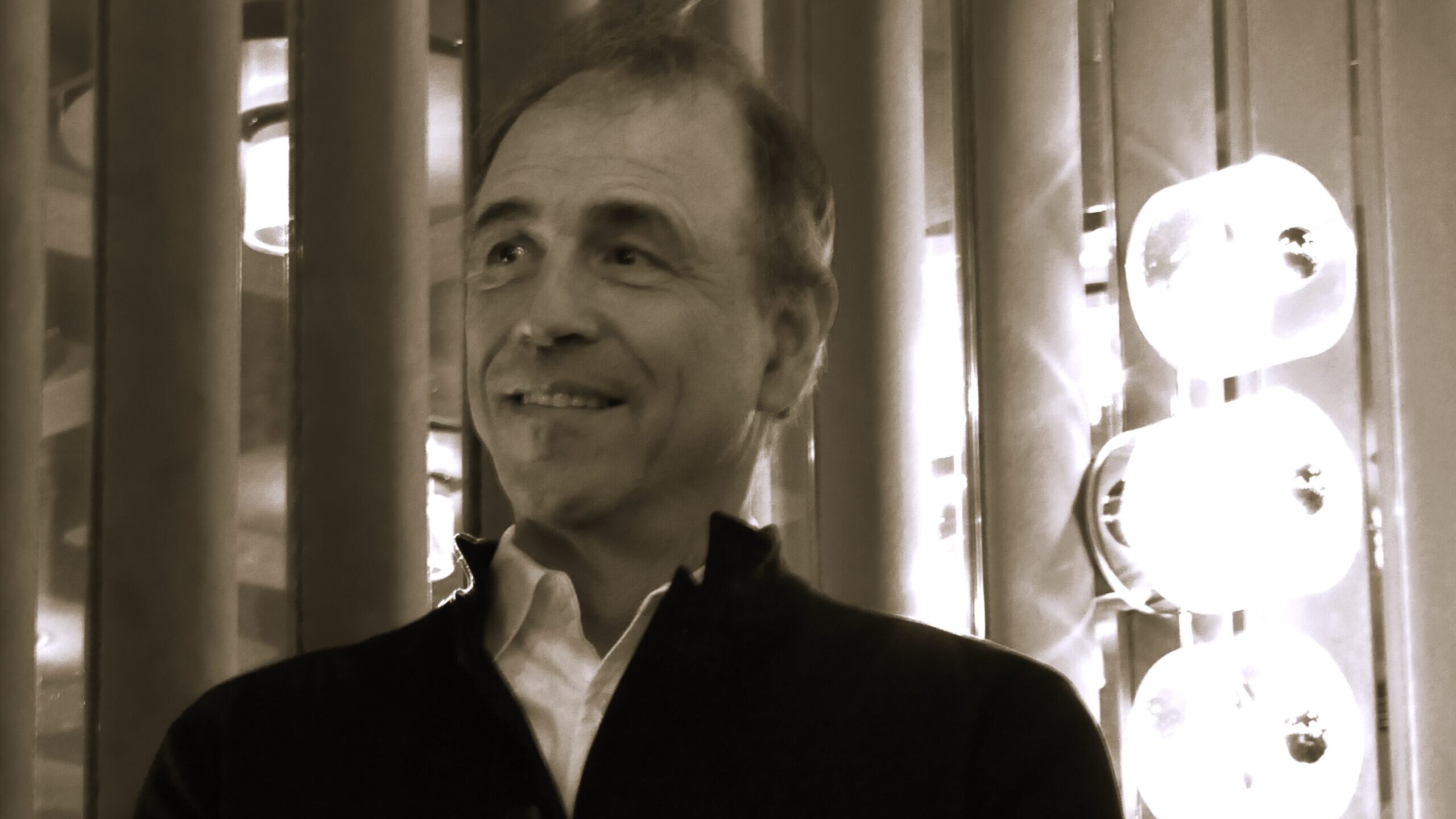

“There is something about Great Britain that is exemplified in this character and which never ever goes away. And which is an incredible achievement. What a hero! And how lucky I am to have written about him three times. He also represents decency at a time when we have so little decency in the political and the societal sphere. Bond always represents – whatever you may think of him – a certain sense of goodness, what we all really want to be.”

Anthony Horowitz, May 19 2022, London

Wholly mindful – just as Fleming himself was – of Bond’s previous adventures, here is a spy haunted by Rosa Klebb, Scaramanga, centipedes, Le Chiffre, Rene Mathis, Wint and Kidd, The Spangled Mob, Fort Knox, Crab Key and all manner of ‘motifs of the mind’. Less a greatest hits cavalcade of 007’s memories, here is an agent quietly desperate to make private amends in a world that has spat him out more than once. As Bond is plunged back into the eye of the KGB storm and an almost surrealist mindscape that sees Horowitz the screenwriter cleverly play with his visuals and production design mind-traps, the author pushes the beats of Fleming’s final novel to mentally haunt and goad our man James. Here is a Bond wholly brainwashed by politics, the state, academia, work and love. And it is pinned to a Soviet Union that is brainwashing itself. But Horowitz knows Bond is better than that. He has to be. And such heroic stoicism lends 007 here a certain warmth of character, amidst the icy machinations and Russian doll subterfuge.

Anthony Horowitz primed to introduce With a Mind to Kill at its May 2022 London launch / Photo © Mark O’Connell

Replacing gold, diamonds and rockets for the value and destruction of the mind, Horowitz’s Bond here is less of the automaton of Fleming’s final novel – and the previous literary dot With a Mind to Kill is keen to become a sibling to. Here, a villain’s predilection is one of aromas and the mind control they elicit. This is a Bond world of truth serums and regretful truths. The undercover Bond is assigned to Russian clinical psychiatrist Katya Leonova – still haunted herself by the absence of “her dark angel” and a beatnik lover rogue one feels Bond would have got on with. The shadowy Stalnaya Ruka (the ‘Steel Hand’) is pulling all their Soviet strings and are even more rogue as they usurp SMERSH under the guidance of both From Russia with Love and Trigger Mortis‘ General Grubozaboyschikov. Or ‘G’ as all western spellchecks prefer to call him. Coy nods to the state-betraying likes of Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean add more espionage grammar to a Bond novel that gradually becomes more narratively duplicitous than they ever were. And whilst acknowledging those ‘Cambridge Spies’ whose own steel hands betrayed British confidences and security, Horowitz threads in real Moscow names too – such as the Soviet security and intelligence minister, Alexander Shelepin. And, of course, the suddenly and aptly cast Nikita Khrushchev himself makes more than a distant impact in the book’s razor-sharp and rather brilliantly frenzied final flight at the Berlin State Opera.

In a mission where treachery is all around and one false move means death, Bond must grapple with the darkest questions about himself. But not even he knows what has happened to the man he used to be.

– Ian Fleming Publications

Whilst Bond is possibly too passive a spy in the book’s middle act, Horowitz is carefully positioning an end-of-career Bond with less momentum in his gunbarrel. A Tower Bridge shootout and extrication happens around him – for good reason. Yet, a duel of strength and identity pinned to the backdrop of the overly ornate Komsomolskaya metro station sees Bond as anything but passive – as Horowitz brings some Red Grant finesse and brutality to a Red Russia fisticuff. This is a The Queen’s Gambit of a Moscow mixed with Horowitz’s own recollections of visiting the city in the early 1970s. Some turns of phrases are not strictly of the era – ‘straight out of KGB central casting‘ – yet this is also not a work penned in 1964. East Berlin’s famed Hotel Adlon is a cracking deorama to the drama – with its nods to Greta Garbo, Grand Hotel (1932) and a Bond who has no choice here, but to be alone.

Just as Ian Fleming cynically, but descriptively side-eyed every street and city he positioned Bond within, Horowitz goes to great lengths to underpin and underline the brutalist world of this cold Cold War post-Fleming Russia and Germany. Culling a few beats and nuances of the Berlin of Fleming’s Thrilling Cities (1963) and a wealth of era-wise research publications, the author is wholly solvent in crafting his icy, Soviet world. And in doing so, he is then wholly able to transport his 007 into that vital Fleming milieu where warmth is scarce and the echoes of a dead wife play less violently than what will happen to Bond’s current female interest. Horowitz gets those willfully detached nods to popular culture that Fleming would drop in, with both his old era disdain and new era fascination (‘she was unable to get the Shadows and the tune of ‘Wonderful Land’ out of her head.’). The 1960s – and Bond’s movie defining decade – is presented here as the bluntly Fleming world of blank safe-houses in Richmond, solitary milk floats, Ford Transit vans, panicked Special Branch personnel and Wolseley cars straight from Horowitz’s own Foyle’s War.

“In With a Mind to Kill, I feel my work is complete. A lifetime as a fan of James Bond reflected in three novels that span his own entire life.”

– Anthony Horowitz

With a Mind to Kill opens and closes on notes of sheer Bond bravura. With our man James ironically aided by a skilled technician of cinema, this third bullet from Horowitz ends on a brilliant flash of nervous peril and a shrapnel cliff-hanger of Cold War uncertainty. Blessed with the literary DNA too of Len Deighton’s The IPCRESS File (1962) and John Le Carre’s The Spy Who Came in From The Cold (1963), Horowitz has carefully layered what nearly feels like a sparse tome into a great, rich spyscape of the mindscape. Quietly brutal and a deceptively blunt instrument of a continuation project, this cold bullet represents a deft last gunshot before Ian Fleming’s Bond celebrates his seventieth anniversary in 2023. Mind-Bonding even.

With a Mind to Kill is available now from Jonathan Cape / Vintage Books (UK) and HarperCollins (US).

Many thanks to Jonathan Cape / Vintage Books.

Catching Anthony Horowitz’s With a Mind to Kill at its London launch.