For the last twenty-five years Steven Spielberg has regularly walked two incongruous movies up the cinematic aisle in close succession. From Schindler’s List and Jurassic Park in 1993, Minority Report and Catch Me If You Can in 2002, Munich and War of the Worlds in 2005, and War Horse and The Adventures of Tintin – The Secret of the Unicorn in 2011 – all have been contrary tales released months apart and demonstrating their director’s ability to not only get a film made and released with swift verve, but also to pursue new stories, genres and tonal shifts. And now in 2018 as audiences wait to enter his VHS, gameplay and pop cultural universe of the much-anticipated Ready Player One (March 2018), we have the very flipside of Gremlins homages, Atari winks and Back to the Future nods in the 1971-set political movie-novella, The Post.

‘So, can I ask you a hypothetical question?’

‘Oh, dear. I don’t like hypothetical questions.’

‘Well, I don’t think you’re gonna like the real one, either. ‘

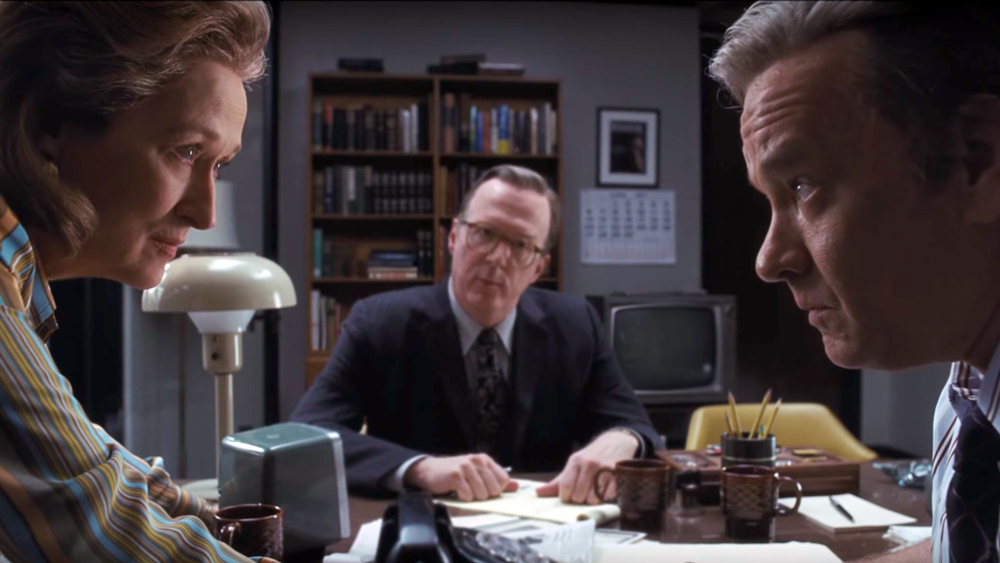

In telling the tale of the Washington Post newspaper in the early 1970s, its owner Katharine ‘Kay’ Graham (Meryl Streep), executive editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks) and passionate staffers, journalists and print men, The Post details the one moment in time when a financially delicate newspaper realises too many boys have gone to war and too many Nixon diktats are silencing free speech and – more pertinently – the truth. Publishing the Pentagon Papers was not just an overture to protecting the press. It was the overture to bringing down one President and questioning the integrity of others before and since. Yet, despite a wide story canvas with some of America’s key 20th Century influencers and political movers in play, one of the early graces of The Post is how it is a curiously intimate recounting of those times.

Launching immediately into the jungle combat and stoner soundtracks of a late 1960s US war, The Post starts out as Spielberg’s first expertly shot and cut Vietnam movie with Brit Matthew Rhys unearthing a political Ark of the Covenant, and ultimately ends where All The President’s Men (1976) begins. Free speech, press freedoms, fake news – there is a big danger with any President or Prime Minister who attempts to stifle institutions bigger than they are, let alone one who claims he invented them all. As 2018 headlines about Russia, emails, collusion and ever-confused White House Press Secretaries’ social and political ignorance spin wildly across our digital devices like 1940s Citizen Kane banners – one of the first observations of The Post is how its times are nothing new. An angry caricature and disgruntled child of a 1971 President shot through a voyeuristic Rose Garden lens is all we need reminding of the current situation. And flawed men are nothing new to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. That is why our storytellers – be it the Washington Post, the New York Times or even Steven Spielberg – must never be flawed in their tenacity or ability to question, to point or to write. The 1971 world of The Post is asked if it would be permissible for D-Day army documents to be made public ahead of time. The curt and precise response reminds how that would have been in hindsight, when the Vietnam War was still fiercely raging. Censuring and censoring the press is about damaging society’s various futures.

‘If we don’t hold them accountable, who will?’

The Ben Bradlee story is particularly familiar to modern American cinema. Jason Robards got a Best Supporting Academy Award for his sterling turn in the role in Alan Pakula’s All The President’s Men (1972). And the Academy gave Best Picture to Ben Bradlee Jr’s real-life show of journalistic integrity in 2015’s Spotlight (2015) – also executive produced by The Post’s Josh Singer (The West Wing). Here, Hanks takes a step aside from the powerhouse of Robards or the moral efforts of Spotlight to work as brotherly, co-worker support to Graham. Under writers Liz Hannah and Josh Singer, both figures never become granite behemoths. Nor are they struggling with the demands of home-life – despite an underused Sarah Paulson who even in her brief, but great scenes with husband Tom Hanks reminds how she could one day close in on the heels of Meryl Streep for a ‘Best Actress In America‘ badge.

From the undulating beams of a midnight photocopier and the light about to be shone on the truth to a reporter having a shoebox of that truth deposited in a panic on his typewriter, a Washington dinner party, a girl wanting her ball back and the preparations of a Supreme Court hearing, cinematographer Janusz Kaminski ensures this is a film often shot at desk height. Those square, Pakula-wise ceiling lights punctuate every newsroom tableau and those wealthy townhouse retreats are straight out of The Exorcist and its Georgetown stairwells and knock-through lounges.

And like the demons of William Friedkin’s 1973 chiller, the orange elephant in the Oval Room is naturally lurking in the west wings of this film. But is The Post some easy, West Coast liberal reaction to the forty-fifth President of the United States? No. Not at all. It is a defence of all writers, artists, principles, and experts – whoever was currently sitting in the Oval Office. An early scene involving the discovery of the magnitude of the papers is set all within an artist’s office surrounded by movie posters, graphic design boards and artistry.

Of course, The Post is aware of its point in history. But so too is Ready Player One. To serve critical writs at a film because it is too aware of its real-life context is missing the point. All cinema does that. And cinema must do that. Spielberg’s Munich was as much about a post 9/11 America as it was a 1972 act of terrorism in an Athletes Village during an Olympiad. Jaws was a post-Watergate movie, not a Creature from the Black Lagoon remake. Yes, The Post is acutely aware of the gender politics in both the workplace – and Hollywood – as it makes a point of dividing the wives from the husbands when the cigars and machismo are pulled out after dessert at a society dinner party in the same way Kay Graham is often pulled out of fiercely male melees by chauvinistic lawyers and company advisors.

‘I’m asking for your advice, not your permission.’

But Streep’s Graham – like the actress herself – is long savvy to the vagaries of gender inequality and shop-floor chauvinism. Streep (in her second Spielberg role after A.I. – Artificial Intelligence) doesn’t play Graham as powerhouse matriarch. This is not a ball-breaking Thatcher in Prada. This is a lead character quivering at the principles and freedoms at stake, rather than her lack of acumen or masculinity. Motherly without mothering, Graham is a press baroness in love with the literal nuts, bolts, and printing presses of her family’s business. Under Streep’s coy, low-key pitch, this film is never about a feminist decision. It is about the right decision.

And as he always has done – and alongside fellow producers Amy Pascal and Kristie Macosko Krieger – Spielberg has responded here with a production marked and blessed by the labours of women. From co-editor Sarah Broshar cutting her way through the ranks on Steven’s last five projects, to art team Kim Jennings and Deborah Jensen and the 86-year-old costume designer Ann Roth (Midnight Cowboy, Silkwood, The Talented Mr Ripley) – The Post’s team both in-front and behind the camera is not saying we need more women. It says they have always been here. You just didn’t pay them enough notice. Or money.

Costume-wrangler Roth punctuates the beige of Washington’s newsrooms with pussy-bows and Gucci patterns (one hilarious tic sees a Post journo unable to efficiently describe to his all-male colleagues what is effectively a tie-dyed dress). Ann Roth is the costume designer responsible for 1970s benchmarks Klute, Marathon Man and Coming Home. So, when Kay Graham is the only woman in the room and frame, Roth – like Streep herself – never stops the press to make a point

Perhaps that last note underscores what is one of The Post’s most unspoken achievements. It is one of Steven Spielberg’s most contained, most precise films. As another Watching Skies skewed movie (The Last Jedi) also recently suggested, The Post is also about the spark and not the fire. Its biggest movie triumph is not an intricate set-piece, an Oscar-baiting monologue or a vicious verbal spat. It is Streep’s Graham saying ‘do it‘ (which got a round of applause at the London premiere) and the middle-aged print room men quietly empowered as they set to silent, but grinning work and a long night. An end coda of flashlights and security concerns in a DC hotel is where the Washington Post’s real veracity and sense of political destiny was to be found. Spielberg leaves that to history and maybe to other filmmakers. Perhaps that is where the most pertinent comment is made to the audiences of 2018 – the free, intelligent and ever-questioning press is there to serve the governed, not the governors. Tell that to every disgruntled press secretary with a Huckabee in her – or his – bonnet.

Ultimately, The Post is about two histories – that of American politics and that of American cinema. For this writer, it is never anything other than an utter joy to see Steven Allan Spielberg return to the decade that made him. If this is a work he produced whilst waiting for the post-production paint to dry on Ready Player One, one wonders what other political stories he has yet to tell… a Vietnam-era Indiana Jones V perhaps?!

Mark O’Connell is the author of Watching Skies – Star Wars, Spielberg and Us (The History Press)

For more photos from the European Premiere of The Post, check out Watching Skies on Facebook.

The Post opens in UK cinemas on January 19th, 2018.

Many thanks to Paul Lofting and eOne.