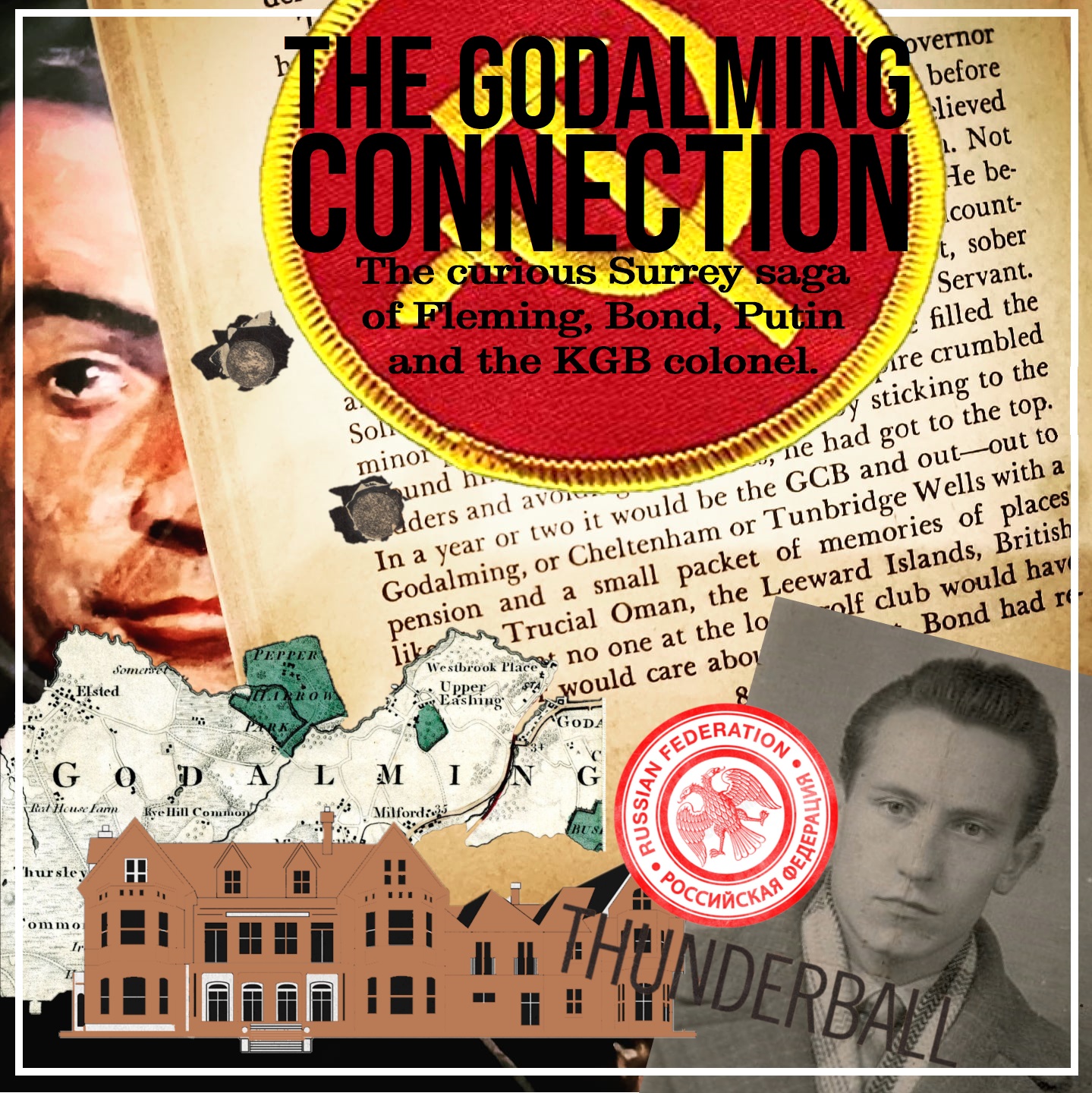

“Out to Godalming…with a pension and a small packet of memories…”– Ian Fleming, ‘Quantum of Solace’, Cosmopolitan, 1959

Ian Fleming, espionage, global politics and James Bond have a shared history with the small English market town of Godalming, Surrey. And none more so historically relevant than right now.

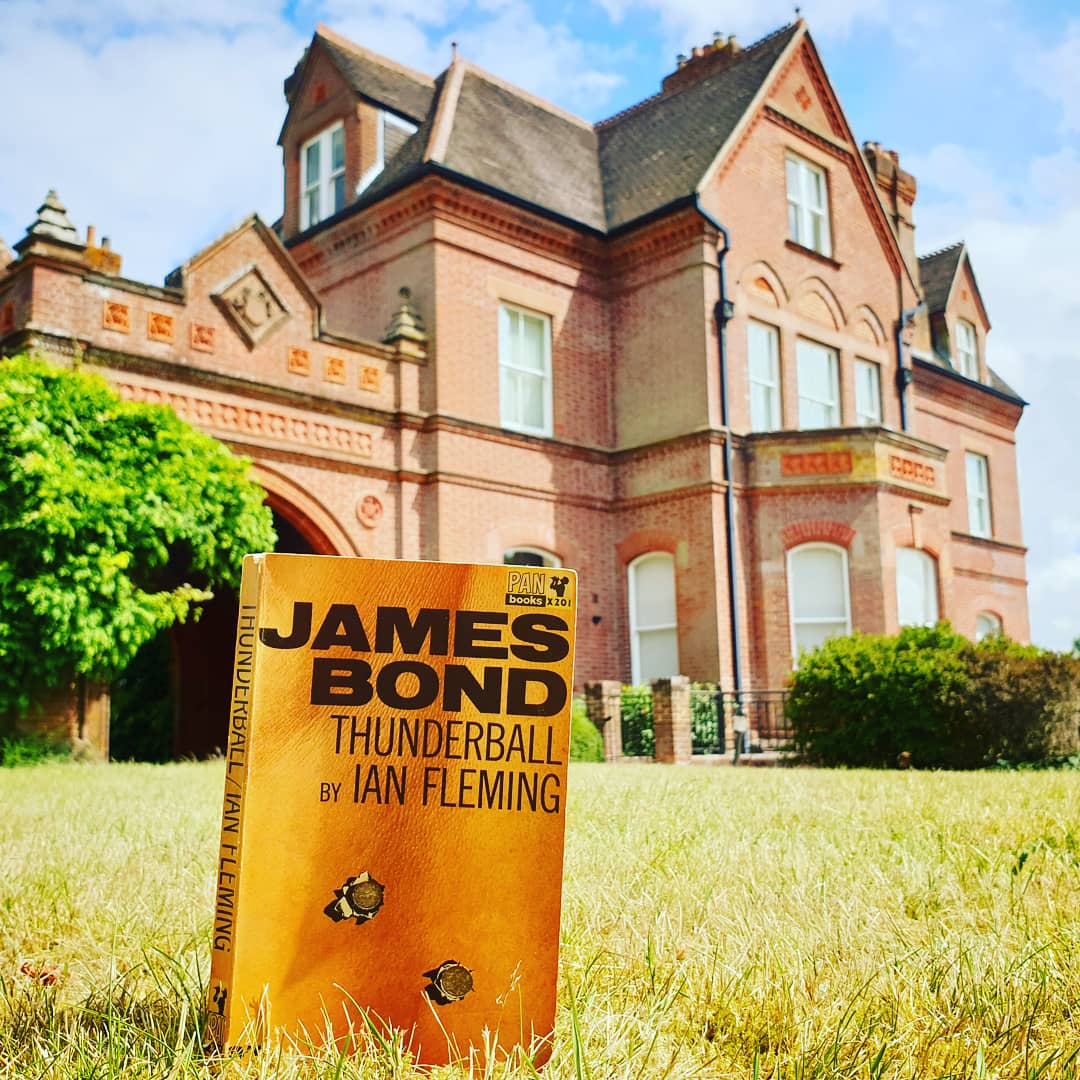

In the spring of 1956 and barely weeks after Diamonds are Forever was first published, Fleming once visited Godalming’s Enton Hall – a then medical rehabilitation centre offering naturopathic treatments. Life and excess was taking a toll and his arteries were tightening. For ten days in April as the Daily Express ran its Diamonds are Forever serialization, the less-keen Fleming endured the health-kick, orange juice assignment his wife Ann had arranged to alleviate her husband from the shrapnel of his lifestyle. She herself had previously visited Enton to address both her fibrosis and barbiturate issues.

“He was allocated one of the chalets in the grounds and became entitled to his statutory glass of orange juice for breakfast, his plate of tomato soup for lunch, his Sitz baths and his massage. He was also given treatment for his sciatica on a traction machine, designed to stretch and loosen the spine.”

The Life of Ian Fleming by John Pearson, 1966

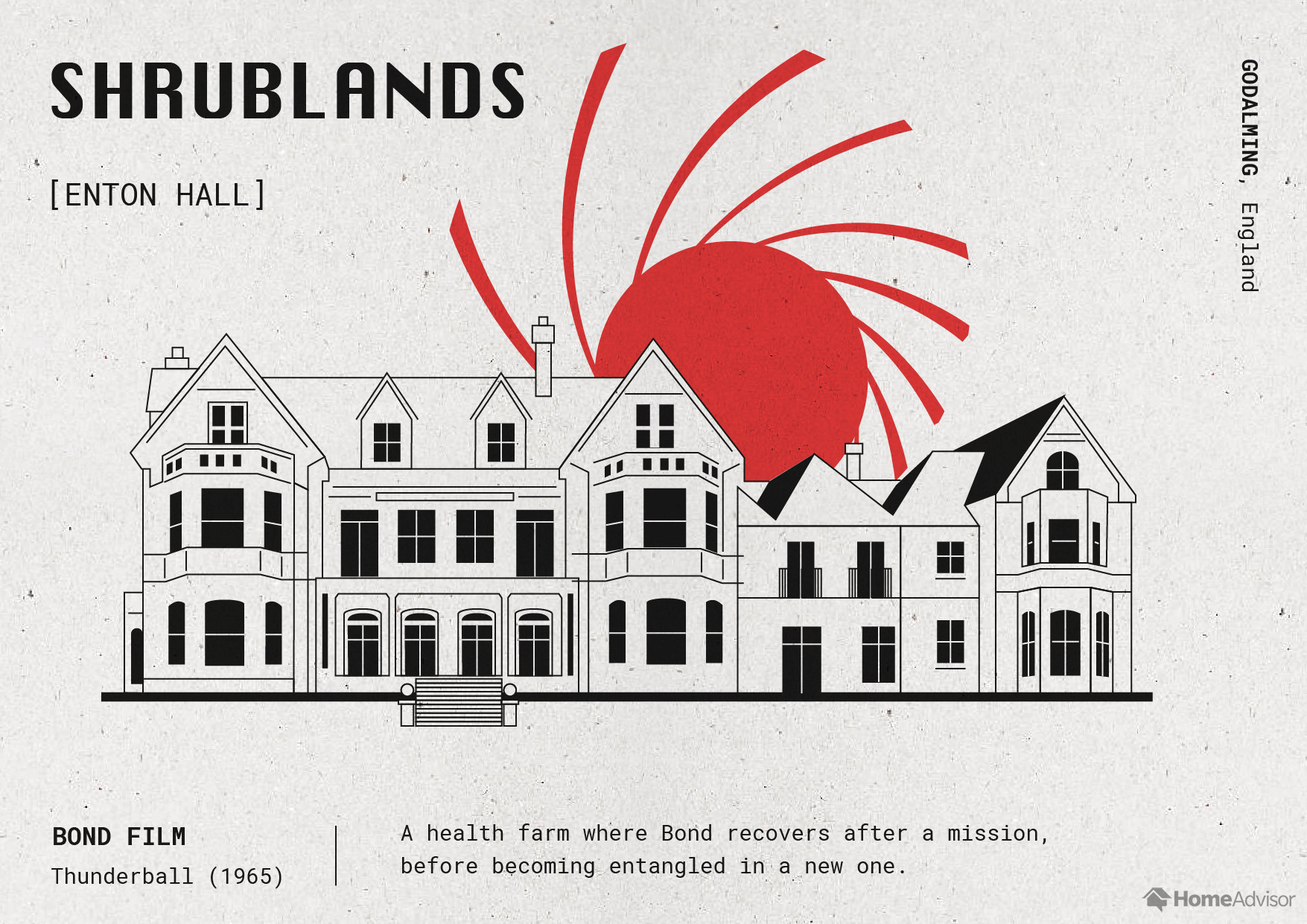

Art by Leonie Wharton / HomeAdvisor

Barely four years later, Fleming used his time at Enton Hall for his ninth Bond novel, Thunderball (1961). Relocating his fictional Shrublands health spa to the neighbouring Sussex rather than Surrey, Fleming took great delight in ramming home the lost-era claustrophobia of Bond’s spa break. “A high wall appeared – ,” he writes, ” – and then an imposing, mock-battlemented entrance with a Victorian lodge from which a thin wisp of smoke rose from the straight trees.” He continues , “… a red brick Victorian monstrosity from which a long glass sun-parlour extended to the edge of the grass“.

Godalming’s Enton Hall also struck a further, influential chord with the spy-maker. Whilst enduring a steam bath, Fleming met a goldsmith from London’s Garrick Street. A prime warden of the Goldsmiths Company, Guy Sinclair Wellby came from a long lineage of royal warranted jewelers and gold experts. Wellby and Fleming became instant Enton Hall pals – taking the afternoons to drive off in Guy’s Bentley and talk about Fleming’s burgeoning fascination in the value, markets, psychology and very nature of all things gold. The mineral features throughout Fleming’s work, yet none more so than his 1959 novel Goldfinger – when Wellby’s insight came into its own. The movie versions of Goldfinger (1964) and Thunderball (1965) transformed the cinematic Bond into a global, pop-culture phenomenon. And both were part-kindled in the leafy enclave of Godalming, Surrey.

Enton Hall later became a golf club headquarters and is now a private residential estate. When pondering the Thunderball ownership saga that rattled through the courts and Fleming’s health in 1963, one name claiming joint parentage over Fleming’s eighth novel was playwright Jack Whittingham. Ultimately co-credited on the film version of the novel, Whittingham went to Godalming’s Charterhouse School as Fleming went to Eton. As did the biographer Andrew Lycett, author of Ian Fleming (1995).

Ian Fleming’s Thunderball (1961) at Enton Hall, Godalming / Photo © Mark O’Connell

Aware of the leafy Surrey commuter belt pin on the map, Ian Fleming would however have been less aware of the lurking, globally significant espionage saga that would later unfold in the market town…

In an ironic echo and twist of Fleming’s 1959 view of the town as a stock-broker retirement cliche, MI6 relocated Gordievsky to Godalming. In the May of 1985, Gordievsky was summoned back to Moscow. But he soon made plans to officially defect to the west he had been working alongside for nearly two decades. The exfiltration operation was masterminded by the head of MI6’s Soviet operations unit, Valerie Pettit. A Safeway bag, a particular Russian street corner at a particular time and a Mars Bar signal formed Pettit’s elaborate, but willfully vanilla plan to help Gordievsky flee the Soviet Union. History has already shown Pettit to be an espionage legend. Remaining good friends with Oleg, Pettit later retired to West Clandon – just thirteen miles from Godalming.

Having been smuggled out of Eastern Europe in the boot of a car – not that long before 1987’s The Living Daylights knowingly echoed the very same trope – and despite a Soviet death warrant on his head, Gordievsky soon became a leading anti-KGB and Soviet Russia mind for anti Kremlin activists, agents and officials. It would of course not make him popular with the Russian high command, despite Oleg being the one who first noticed the later leadership qualities of a man called Mikhail Gorbachev. Tit for tat expulsions of diplomats, spies and British nationals ensued in both London and Moscow.

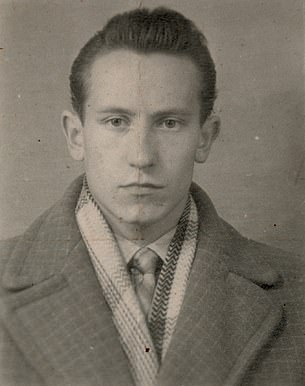

In the height of the 1980s Cold War and just as A View to a Kill (1985) was firing at movie screens (based very loosely on another short story from the same For Your Eyes Only collection that Godalming saw its flippant namecheck), famed former KGB colonel Oleg Gordievsky revealed to the world how he was in fact working as a double agent for the British Secret Service. Gordievsky had purportedly helped keep the West from various Soviet era threats, including nuclear attacks and a small matter of World War Three. As Roger Moore was battling the 1970s Cold War onscreen and a young Russian called Vladimir Putin was joining the KGB, Gordievksy was passing Russian secrets to MI6 under the codename Sunbeam. In a 2003 paper titled ‘Fictional Figures and the Historian – The Politics of James Bond’ the historian Jeremy Black (The World of James Bond – The Life and Times of 007, 2017) recounts how “Gordievsky claimed that the Central Committee of the Communist Party watched James Bond films“. That is wholly understandable. The White House famously did the same – with 1963’s From Russia With Love being the penultimate film John F. Kennedy watched before his November 1963 assassination (The Special Bond – Catching all the presidential men and their relationship with 007). However, the Bond movie nights in Moscow were less about entertainment and more about intelligence. As Black notes, Gordievsky “was instructed to “secure a copy as soon as one came out. The KGB also asked him to obtain the devices used by Bond.” A few years later and on July 24 1987, the self-declared Bond fan President Ronald Reagan held a screening of The Living Daylights at Camp David. Just three days before he had met with Oleg Gordievsky at The White House.

‘[Gordievsky’s] remarks serve as a reminder that popular culture is not a distinct subject, widely separated from the real world of politics, but instead, a factor that helps to shape the latter just as it is shaped by it.’

‘Fictional Figures and the Historian – The Politics of James Bond’, Jeremy Black, 2003

Oleg Gordievsky in his student days.

In 2006, a former officer of the Russian Federal Security Service seeked the advice and counsel of Gordievsky. The man was called Alexander Litvinenko. He was also on the radar of Moscow and the Putin administration. Since moving to Britain officially in 2001, he had come down to Surrey from London around seven times. Yet, the 2006 trip to Godalming was also the last. In November of that year, Litvinenko was fatally poisoned. The trail of the Putin-sanctioned polonium that was aggressively killing Litvinenko was alleged to have also been traced to Godalming and Gordievsky’s residence. Once again, Alexander had visited Oleg in the town for empathic advice, yet his fate was tragically sealed. Gordievsky made it known he believed Vladimir Putin or associates close to him were responsible for the death.

A year later after Litvinenko’s murder, Britain awarded Oleg the Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George. In the From Russia with Love (1957) novel readers are told how James Bond was awarded the same honour four years before. In 2021, actor Daniel Craig was also gifted the CMG for his services to culture and cinema.

In 2018 author Ben Macintyre (For Your Eyes Only exhibition, Imperial War Museum, 2008) wrote The Spy and the Traitor – The Greatest Espionage Story of the Cold War. It is the courageous, game-changing tale of Oleg Gordievsky – who Macintyre believes did more damage to the KGB than even 007 himself. He also discusses Valerie Pettit. With further death attempts on his life since, Gordievsky remained in Godalming. As do – rather curiously – a sprinkling of oligarchs and their alumni. Gordievsky even survived Raoul Silva. In the spring of 2012, Skyfall built and shot its epic Scottish finale on Hankley Common just outside Godalming. In 2020 the Russian-centric The King’s Man (2021) and Black Widow (2021) also shot on the same stretch of heathland. Eight decades before, Hankley Common was used as one of the D-Day training grounds – with some of the mocked-up Atlantic Wall still standing amidst the heathland, and all lit up by the record-breaking pyrotechnics the spring night EON Productions blew up Skyfall Lodge. The British Army and their helicopters continue to use the Ministry of Defence land to this day.

So, despite Fleming’s 1959 suggestions to the contrary, a Godalming retirement for those in the espionage business – be they real or fictional – held more than a “small packet of memories” that “no-one at the golf club would have heard of or heard about.”

Oleg Gordievsky passed away in March 2025, aged 86. Counter terrorism police assisted the coroner, but feel no foul play was involved.

Silva’s Merlin helicopter circles Skyfall Lodge as the eyeball helicopter surveys the impending action on the heathlands of Surrey / Photo © Mark O’Connell

Sources:

‘Fictional Figures and the Historian – The Politics of James Bond’, Jeremy Black, John Hopkins University Press, 2003

GoldenEye – Where Bond Was Born: Ian Fleming’s Jamaica, Matthew Parker, Windmill Books, 2015

The Life of Ian Fleming, John Pearson, Jonathan Cape, 1966