“It is with such sadness that I heard of the passing of one of the true greats of cinema.’

Daniel Craig

(This article was originally part of an article by Mark O’Connell / Yahoo Movies)

Until 1962’s Dr. No, action cinema was the commonplace realm of jingoistic war movies, ailing backlot westerns, biblical excess, and tired thrillers. Yet, when an English author, a New York movie producer and a Canadian showman walked into a movie deal to bring James Bond 007 to the big screen, their cinematic vision of an adventurer spy had the potential to overhaul a genre. When they finally cast Sean Connery in the autumn of 1961, they went one better. They transformed cinema itself. A massive part of that success was Sean Connery himself – a new era player from a pool of new British young men changing how mainstream matinee cinemas was cast, watched and produced.

As the Mods went to Brighton, The Beatles sailed to Hamburg and bright young British things began dominating 1960s culture, movie audiences sought a new wave of British cinema and representations. Suddenly, working-class heroes like Albert Finney, Alan Bates, Tom Courtenay, Terence Stamp, Richard Harris and Michael Caine had box-office validity over the Cary Grants, James Stewarts and David Nivens. On October 5th 1962, two moments happened on the very same day. One was The Beatles released ‘Love Me Do’. The other was that Dr. No premiered in London and introduced the world to what would become the first knight of action cinema, a rare British movie star and the very DNA of 007 – Sir Sean Connery.

Curiously fuelled by Bond producer Harry Saltzman pre-007 success with titles such as Look Back in Anger (1959), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1961) and A Taste of Honey (1961) – it wasn’t now a total gamble to speculate on an unknown by the name of Thomas Sean Connery for one of cinema’s most sought after roles. The Fountainbridge kid that had once delivered milk to Edinburgh’s Fettes College was now about to play its most prominent fictional alumnus.

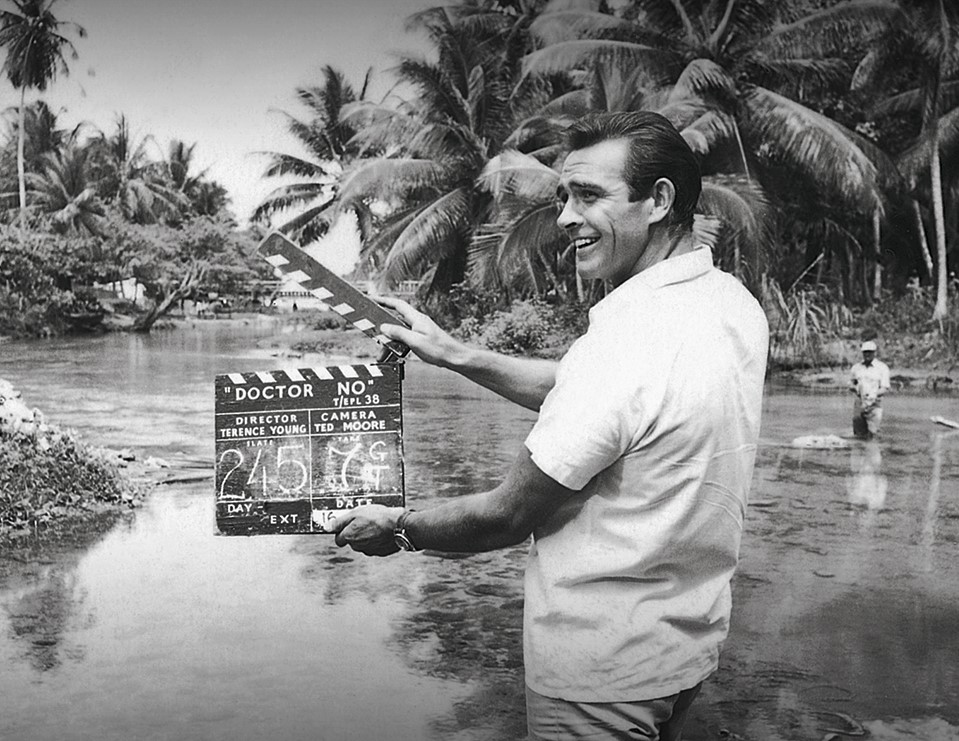

As the inaugural Bond has died it cannot be overstated just how Connery’s 007 revolutionized the pace and gait of action cinema. With a heady creative mix of director Terence Young, editor Peter Hunt, stunt choreographer Bob Simmons and designer Ken Adam empowering Connery to bring that panther fortitude with a modish skip and bounce to the screen, the first Bond movie Dr. No was a prototype both for 007 and action movies. Marked by staccato editing, a jet-set sense of physicality and sexuality and the Broccoli awareness of placing B-movie beats in A-lister tailoring, Dr. No very soon kicks away the colonial trappings of a 1950s Britain as we met Connery’s Bond – and the nifty conceit he has been in the job for a while and wilfully younger, more agile than his onscreen cohorts.

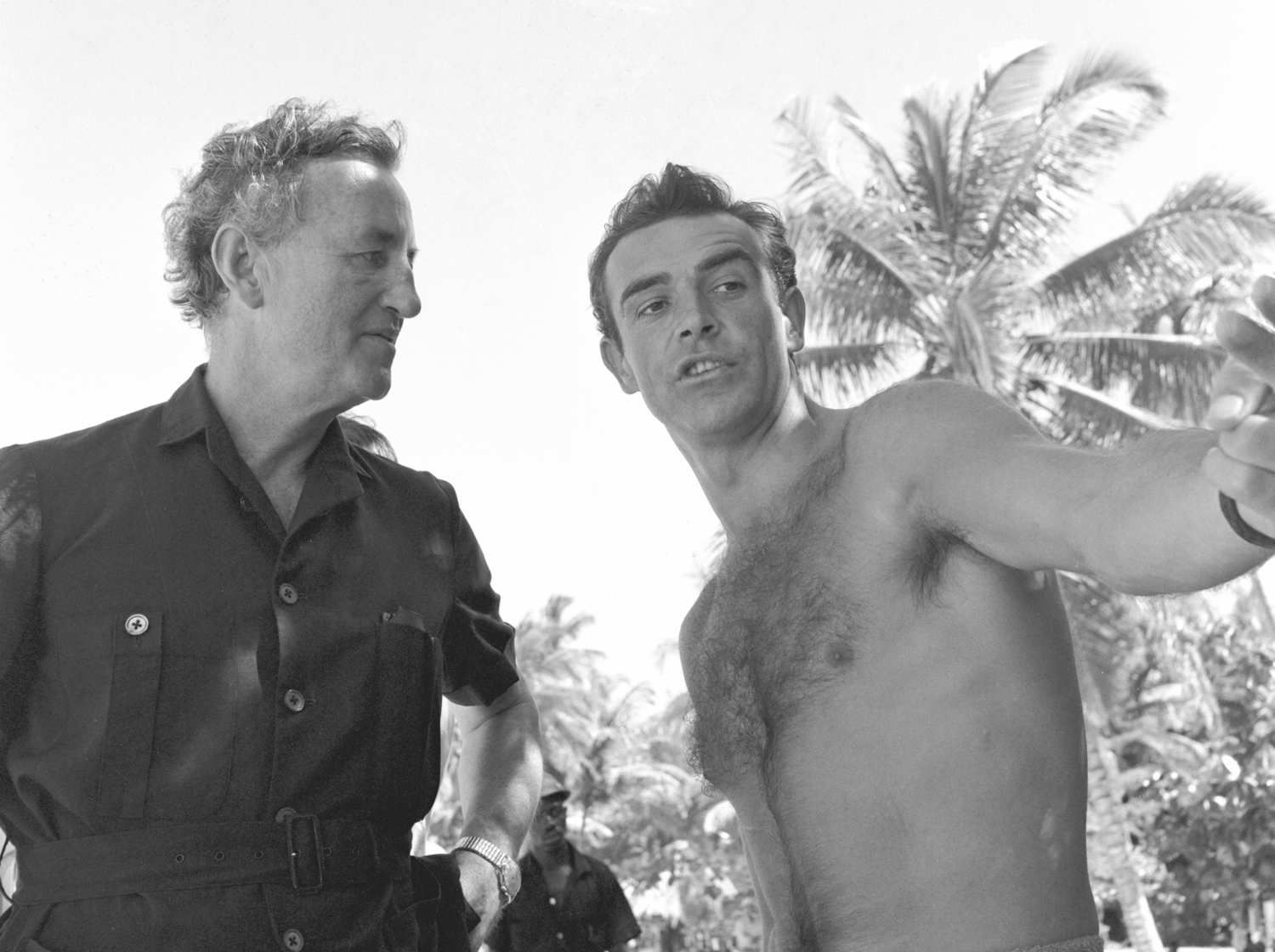

The creator meets the icon as Ian Fleming and Sean Connery spent some Jamaican time together during the 1962 shoot of Dr. No

By the time of Goldfinger (1964) and the third spin of the Bond dice, the prototype was now a golden template of movement, style, physicality, sex, and design. And at the heart of that was an actor who was about to tire of the character and look over his shoulder at Hitchcock, Lumet, Hollywood, European filmmakers, and independent cinema for new roles. What often gets lost in time is just how globally known Sean Connery was in the role of Bond. Possibly pop-culture’s 007th Beatle, Connery’s working life was then an overwhelming circus of airports, press calls, paparazzi invasion and headline baiting rumour. That takes a toll on any soul. Fortunately, Connery had ways of distracting himself and often turned to the arts, his creative friends and the valuable calm it afforded him.

Connery was rarely a Hollywood outsider. Screen legend and co-star Lana Turner first introduced him to Bond captain Albert R. Broccoli, he went from Disney’s Irish blarney (Darby O’Gill and the Little People, 1959) to Hitchcock’s Marnie (1964), Fox’s The Longest Day (1962) added him to the longest cast list of Hollywood’s greatest and he became a Sidney Lumet regular (The Hill, The Anderson Tapes, The Offence, Murder on the Orient Express and Family Business). But the shadow of that tuxedo stretched wide. And for Connery himself more than perhaps anyone else.

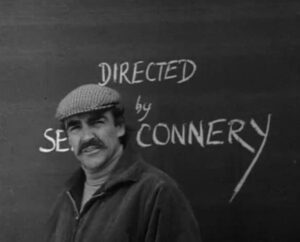

Connery’s only directing stint, The Bowler and the Bunnet (1967)

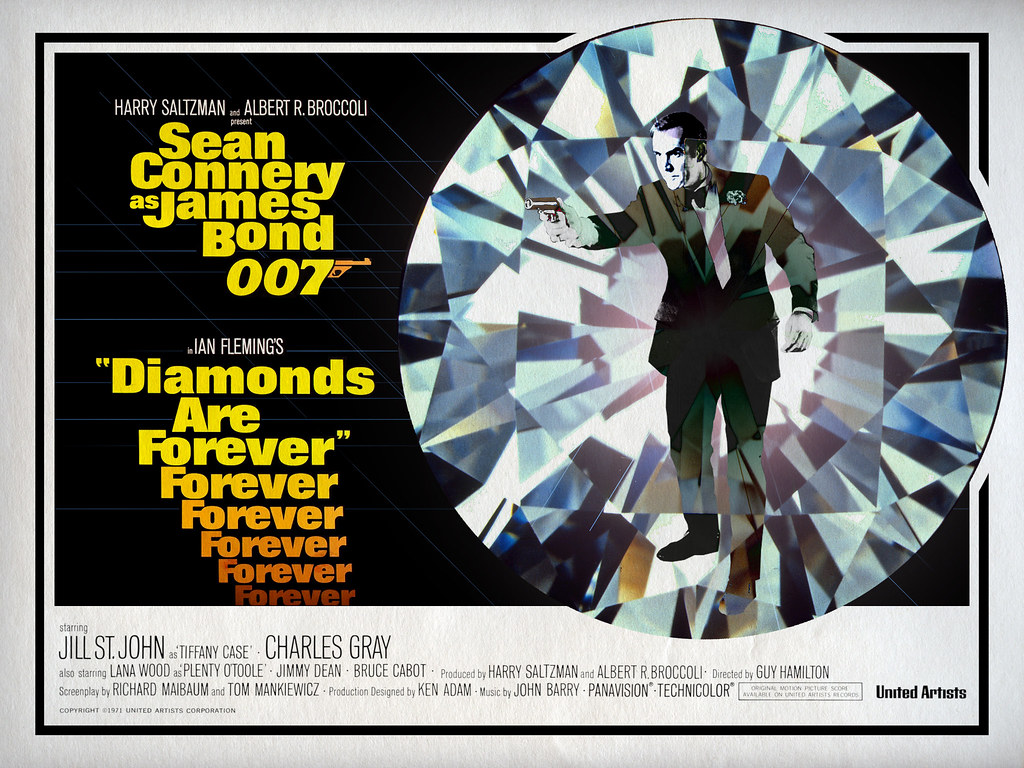

Ironically, returning to the role he wanted to shake off the most oddly enabled him to have a 1970s and 1980s that did just that. It can be reasoned his comeback Bond stint for Diamonds are Forever (1971) – and its pop-cultural digs about a Vegas world populated by people past their prime in an entertainment system that can spit you out – inadvertently proved the older, less panther-like Connery was still a box-office player who was easily now more Sean than James. Initially, Diamonds was followed by titles that held less action and were more aligned to Connery’s learned social conscience and his passionate grip on culture, art, and politics. His only directorial work The Bowler and the Bunnet (Scottish Television, 1967) was a shipyard documentary starring Sean himself and written by famed Glasgow chronicler Cliff Hanley who had won the Best Live Short Academy Award for another industrial ode to Glasgow. That curious straddling of LA business and blue-collar narratives continued to mark out Connery’s 1970s.

The Molly Maguires (1970) looks at 1880s Pennsylvanian miners through a western branding. The abuse subject matter of The Offence (Lumet, 1973) balances out the Bullitt minded caper-jinks of The Anderson Tapes (1971). Hijack thriller Ransom (1974) granted gun-clutching poster ops for Connery as desert forays The Wind and The Lion (1975), The Next Man (1976) and one of his best, The Man Who Would Be King (1975) mixed period swagger with colonial comment and a clearly happy, 007-distant Sean.

Perhaps the most overlooked Connery film of the 1970s was Robin and Marian (1976). Richard Lester’s autumnal elegy to another British cultural icon growing older completed the suggestion Diamonds Are Forever had made five years before – that Connery’s greatest career upsurge would come from playing the mature action lead and the seasoned elder. And just as the 1970s were marked by Connery returning to Bond, so too were the 1980s.

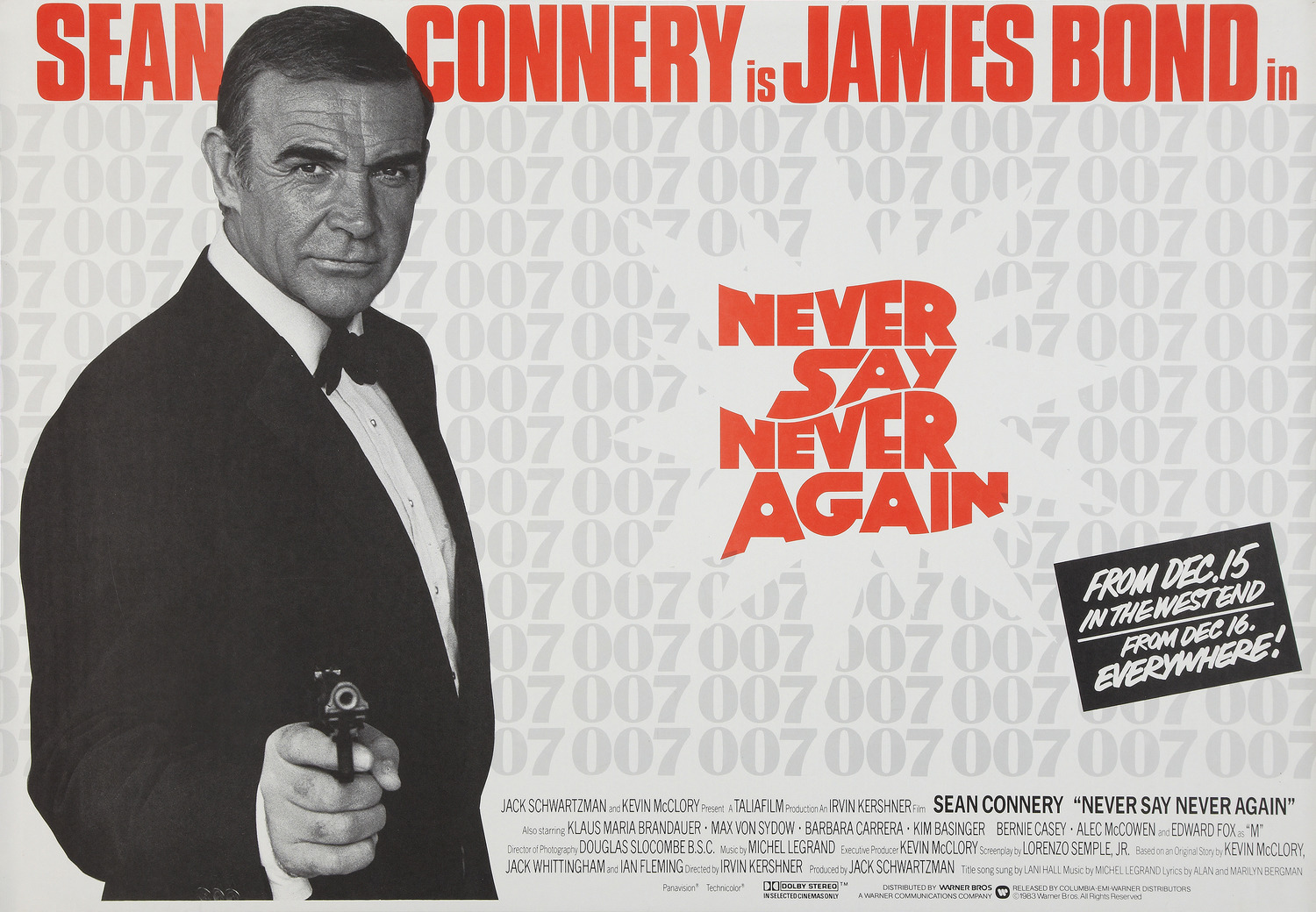

His reasoning for returning to a rogue 007 film and the fingers-up which Never Say Never Again (1983) represented to the very House of Bond that launched the actor was no doubt manifold. Ownership, authorship, egos, creativity, bank balances and time are strange bedfellows in Hollywood. The headlines may suggest cash incentives and loyalty-crushing twists, but maybe Connery actually had an ownership on the role that the world didn’t wholly fathom. Bond may have made him, but Connery also made Bond. And that knowledge creates traction.

Whilst some could suggest Connery fled 007 on a bungee rope, his two cinematic Bond revivals proved invaluable manoeuvres in again taking forward the bankability of action Sean. With Outland (1981) and Time Bandits (1982) as veteran starting blocks, it was Highlander (1986), The Name of the Rose (1986) and his Academy Award winning return to blue-collar heroes with The Untouchables (1987) that the cult of Connery really soared. He won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for the latter role and the warmth and fun the Oscars had from his appearances at the time attested to the fondness Hollywood had for its rogue and brogued Scottish prince with a taste for golf, the Bahamas and art.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) and The Hunt for Red October (1990) represented marquee name glory and global love, John Le Carré’s The Russia House (1990) was a career high, a middling medieval triumverate of Robin Hood – Prince of Thieves (1991), First Knight (1995) and Dragonheart (1996) saw him really run with that icon baton before the underrated The Avengers (1998) allowed him to play a Bond villain.

Whilst Entrapment (1999) is easy fun and The League of Extraordinary Gentleman (2003) is a sad and final mess, it is Connery’s role as an ex-SAS captain in The Rock (1996) and its quiet Bond nods and exchanges that fittingly tops the actor’s movie tenure: with a fittingly action-led flourish, his globally-functional Scottish brogue and the ever wild hairpieces.

Art by Sampard Art

James Bond did not afford Connery the opportunities to continue working. It enabled him to make choices. Choices that saw him work with old and new Hollywood, European masters, Sixties pioneers, blockbuster captains, homeland poets and indie unknowns. As Daniel Craig now straddles three decades as 007, Sean Connery still has the glory of filling the role over four – the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and for a 2005 computer game (EA’s James Bond 007: From Russia with Love). But it is Connery’s Bond that is forever bound to the memories of cinema we all have. Connery represented kids and dads watching movies together – whether down the picture house, the drive-in, on VHS or a rainy Sunday TV afternoon. Connery represented the escapism of a jet age, the color of travel, the tailoring of masculinity, the potential of a new Britain and the new pop-art style of a new guard that once took over the cinema lobbies and marquees. And then when Connery himself became the old guard, his work and Bond films were suddenly those cool new vinyl treasures our parents got us into or who we point all younger movie fans towards.

The biggest screen hero of the decade that modernized a post-war world, Sir Sean Connery may have pressed the Bond ejector seat button more than once. But when he did, he was thrust higher than all his 007 successors combined.

Rest in peace, Sir Thomas Sean Connery. Go and find Domino, Pussy and Dink and shake them a Vesper. This article was originally part of an article by Mark O’Connell / Yahoo Movies.

Art by AZ