‘A man comes. He travels quickly. He has purpose. He comes over water. He travels with others. He will oppose. He brings violence and destruction.’

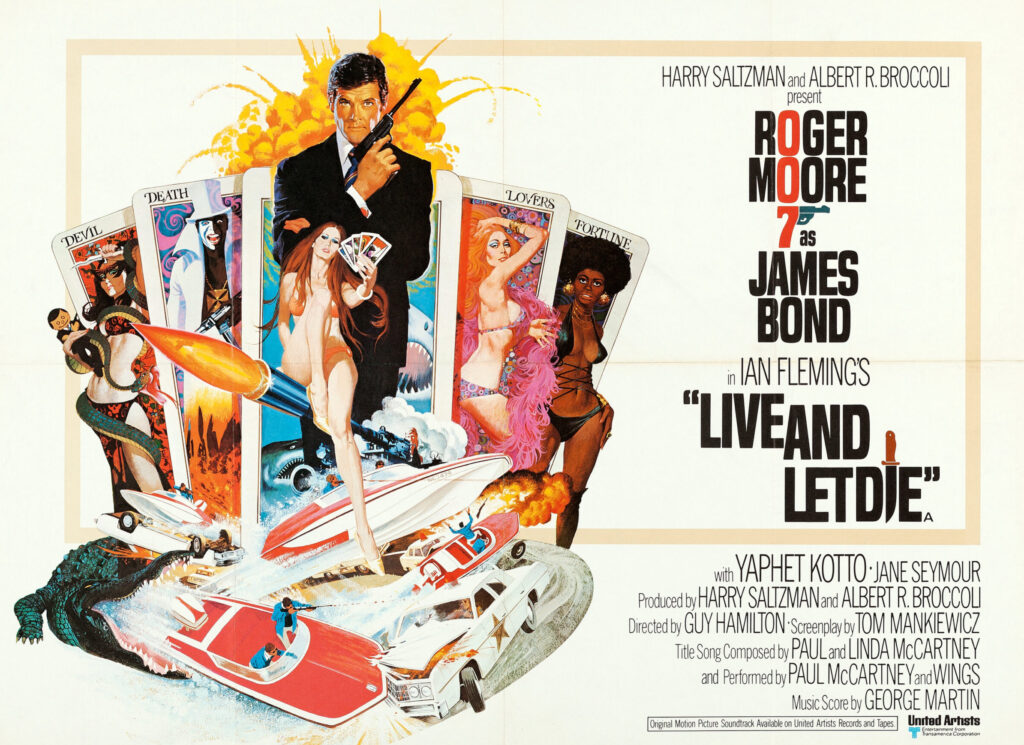

live and let die / 1973

‘There is a simple, barely important moment when Roger Moore’s Bond is in Leiter’s New York apartment and being re-dressed by a voiceless aide. As Felix Leiter (David Hedison) is diffusing an off-screen situation caused by 007 accidentally destroying a small airport, Bond turns to an aide clutching a fine selection of shirts and ties for his sartorial usage. “That’s fine” says Moore, “You can fit the rest this afternoon. Don’t forget the double lengths. That tie will do nicely, that’s a little frantic and keep the other three”.

That tiniest of asides speaks volumes about the buoyancy and poise Moore brought to Bond. The difference is that this is barely half-way through his first 007 film and he is already wearing the role like one of those perfectly chosen ties. Very few Bond actors have the grammar of their overall performance already in place on their maiden voyage aboard the good ship EON.’

– ‘Live and Let Die’, CATCHING BULLETS – MEMOIRS OF A BOND FAN

When it held its world premiere on July 5th 1973, the vital Live and Let Die finally introduced Roger Moore to the 007 role – and soon became a rare Bond bullet as it is one of the few the wider public vividly recall (helped partly in the UK for being one of the highest watched films on TV of all time).

Heavily aided by screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz’s delicious writing and dialogue and a repeat of Diamonds are Forever’s winning hook of positioning Bond as a mismatched fish out of water, Live and Let Die is a leopard-skinned travel case packed with fresh and sardonic invention. Contrary to belief, director Guy Hamilton did not set out to solely make Bond’s blaxploitation caper. He set out to make The Godfather in Harlem – with its connected world of dandy gangsters, tailored menace and whispered corruption.

Born in 1922, Guy Hamilton was the second director to shape Bond’s cinematic journey. When he came on board to direct the first real designer bullet of the Bond series (1964’s Goldfinger) he steered a 007 adventure that would define everything that came after. Goldfinger did not just redefine Bond on his third spin of the movie wheel. It redefined action cinema. Hamilton’s subsequent Diamonds Are Forever, (1971), Live and Let Die (1973) and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974) were not just further entries in Bond’s cinematic output. They were the films that Hamilton enabled Bond in the 1960s and 1970s to fully echo the timbre, beats and essence of the decade they had to cinematically dominate.

After a seven-year gap, Hamilton returned to direct Sean Connery’s [first] last spin of the Bond dice, 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever. He then continued and bedded Roger Moore into the role with the subsequent Live and Let Die (1973) – and returned for its sequel, The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). In all his Bond work including Live and Let Die, Hamilton gave Bond a cinematic head-start for two decades where 007 had to be at the top of his movie game or he may well have floundered at the box office. Just as Goldfinger lent Bond his momentum, Live and Let Die holds a new era physicality. The boat chase alone is shot for real instead of a Pinewood blue screen.

There is also a deceptive amount of audience pleasing kit and apparatus in Bond ’73. A downtown Harlem Fillet Of Soul bar-booth becomes an ingenious portal to Kananga’s underworld HQ, CCTV-eyed scarecrows and car wing mirrors spit poisoned darts, coat hooks on boats activate hidden below-deck bureaus, shaving foam canisters become flame throwers, inflatable bullets cause sofas to swallow henchmen in one gulp, magnetic watches undress an Italian agent before converting into mini buzz-saws and the random likes of a flute and a shoe-brush become all manner of microphones and intercoms. These are all fantastical touches that play to and hook the younger audiences alongside the slightly more adult keynotes of deflowering Jane Seymour, voodoo murders, heroin consumption and Roger Moore’s bare nipples for all to see.

It is arguable that two of the Bond titles often cited when fans are asked ‘which one should I play to introduce someone new to 007?‘ are both Hamilton’s Goldfinger and Live and Let Die. They are the titles named by non-fans as they place Bond as the audience, a recurring British fish out of water battling new cities, new cultures and new technologies – be it Las Vegas or Thailand or Harlem.

Blessed with cracking dialogue, sense of purpose and pacing from writer Mankiewicz, Live and Let Die is also a rich caper that privately weathered a less public rift between founding producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman. When EON Productions and Cubby went solo with 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me, it was Hamilton who ensured the series was left in a solid enough place for the public – and EON’s – confidence to move forward. Live and Let Die was a key part of that. As was its score. As was Paul McCartney’s anthemic title song that is still a Glastonbury stalwart fifty years later.

‘The dragons have changed. Fleming was always writing about the Russians as the villains and the Cold War. But life has gone on. And so the problem these days is to find the dragon because Bond is St. George. Ultimately, he is killing dragons for the benefit of mankind.’

GUY HAMILTON, 1975

Rather than poolside villas, colonial hotels and lavish lobbies, in Live and Let Die we have pared-down apartments, parking lots, back-alleys, basements, fire-exits and poky voodoo gift shops. There is potentially more minutiae of the average man on the street’s world than any previous Bond film, the costume design overshadows the production design and its creepy malevolence and blood red production palette make it the only Bond bullet to step into a horror genre all of its own.

Although he was older than Connery, Moore’s investiture as 007 sees a leaner and fresher Bond in a film that wants to press the reset button. But as two 007’s had come and gone in the previous two Bond movies and a great deal was riding on Bond ’73, Live and Let Die secured the 007 franchise by astutely playing out like Roger Moore has been doing it for years. Names are for tombstones, granted. But fifty years on, Live and Let Die is still that young Bond film with a franchise heart like an open book.